Tags

David Michôd, Falstaff, Henry V, John Edgerton, Kings and Queens, Medieval England, Medieval Europe, Shakespeare, The King, Timothée Chalamont

Last night I watched The King (2019, dir. David Michôd), which is loosely based on Shakespeare’s Henriad cycle about Henry IV and Henry V. It’s a gloomy, dreary film in which color wasn’t invented until long after Henry V’s reign was over. Even the cloudless sky seems dreary on the rare occasions it appears. In case you can’t tell, I didn’t love it. So let’s get into why.

The Henriad

The King isn’t really based on historical fact. It’s based on the Henriad. Joel Edgerton and David Michôd decided that they wanted to tell a story that was based on Shakespeare but without being Shakespeare. Basically, they wanted to show that they could do Shakespeare better than he did. And they failed.

For those who haven’t seen the plays of the Henriad cycle, Henry IV Part 1 introduces us to Henry IV and his dissolute son Prince Hal, who has a circle of wastrel friends centered on Sir John Falstaff. Henry and Hal have to deal with the revolt of the Earl of Northumberland and his hot-headed son Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy. The play culminates in a fight in the battlefield between Hal and Hotspur, in which Hal kills his opponent.

Henry IV Part 2 picks up where the previous play ends and follows the revolt against Henry, which gets put down. Falstaff spends the play in various misadventures and dealing with his worsening health. Hal reconciles with his father as his father dies, and when Falstaff comes to Hal, expecting rewards from the now king, Hal disavows him.

Henry V deals with the early phase of Henry’s reign. Falstaff dies off-stage, Henry puts down a conspiracy against him, and then embarks on the conquest of France, culminating in his victory at the battle of Agincourt, after which he ‘woos’ Katherine, the daughter of King Charles VI of France.

The King manages to fit all of this into a single movie, although it sharply compresses the material from Part 2. The result is a movie that tries to be a character study of the young Henry. But it’s not the historical Henry they are studying; it’s the literary Henry, but they’ve made changes, so that the film isn’t really based on either the historical Henry or the literary Hal, but is actually a weird sort of What If scenario. What if Hal had reconciled with Falstaff instead of his father but had still managed to realize his potential as a leader and had managed to rehabilitate Falstaff? Oh, and What If Falstaff had been a real person?

Prince Hal’s Youth

The film starts roughly where Part 1 starts, with Young Henry (Timothée Chalamont) being estranged from his father Henry (Ben Mendelsohn) and close friends with Falstaff (Joel Edgerton). He is first seen lying unconscious in a bed after a wild bender the night before, setting up the idea that Henry was a party guy in his youth.

There is, however, no real factual basis in this; Hal’s wild and dissolute youth is best known from Shakespeare, who was drawing off a slightly earlier anonymous play called The Famous Victories of Henry V, in which Prince Hal is basically depicted as a thug before becoming king. The historical Henry was already playing an important role in government by the time he was 14, when he started acting as the Sheriff of Cornwall, an essentially administrative office in which he would have had underlings to help him. He got the office in 1400, soon after his father deposed Richard II and made himself king. In 1402 young Henry joined the Great Council, one of the most important organs of royal government.

Chalamont as King Henry. At least the haircut is kinda accurate.

In 1403, young Henry led an army into Wales to help put down the revolt of Owain Glyndwr. Shortly after that, he met up with his father’s forces at Shrewsbury and helped put down Hotspur’s Rebellion. Exactly what happened to Hotspur is not clear; he was either killed by an unknown opponent or by an arrow when he opened his visor to get a better view of the battlefield. He was almost certainly not killed by Prince Hal (as the film shows), because Hal had gotten himself horrifically injured; he had been struck in the face by an arrow, the head of which had lodged under the skin below his left eye close to the nose to the depth of 5-6 inches, miraculously without hitting either the brain or any of the arteries. John Bradmore, the court physician, was able to devise a special tool to remove the arrowhead several days later and managed to prevent infection by flushing the wound with alcohol. The result was that Henry survived but with a horrible scar (which no cinematic Henry has ever sported).

Henry spent the next decade fighting Glendwr in Wales, and was recognized as basically being in charge of Wales and the effort to pacify it. Records show that was he very interested in the details of sieges, for example writing letters demanding shipments of wood for siege weapons. By 1408, his father’s illness (which involved skin infections and attacks that left him incapacitated for long periods) was making it harder and harder for him to run the kingdom. As a result, between 1408 and 1411, Young Henry was playing an increasingly central role in government via the Great Council, which was taking on a larger and larger role in decision-making. In 1411, he had a falling-out with his father over policy issues and was dismissed from government. There were rumors that he was trying to depose his father, but the evidence for that is weak, although the matter was serious enough that it provoked a meeting between father and son at which Young Henry handed his father a knife, say that if his father wished to kill him, he would not stop it. But there was never any serious question of him not succeeding his father, which he did in 1413 when the older Henry finally died.

Claims that he had a riotous youth rest on very shaky foundations. His brothers were involved in a brawl in an Eastcheap tavern in this period, but Henry himself was not a party to it. Contemporary chronicles say vaguely that he was devoted to “Mars and Venus” (violence and sex), but give no real specifics. The chronicles also remark that he had a dramatic conversion of personality when he was became king, but medieval chronicles were inclined to exaggerate such things to make better stories, and given the lack of any specific details, it’s unwise to suggest that Henry was a hellion.

Oldcastle and Falstaff

From an historical standpoint, the biggest problem with the film is Falstaff, who plays a much larger role in The King than he does in the Henriad. As I already noted, in Part 2, the new king Henry repudiates Falstaff, whose health is in decline. He dies off-stage very early in Henry V. But in The King, not only does Henry not repudiate Falstaff, he relies on him because he knows that Falstaff is going to be honest with him and not just flatter him. That’s a pretty sharp difference from Shakespeare’s Falstaff, who is absolutely the kind of man who would flatter and suck up to Henry to advance himself.

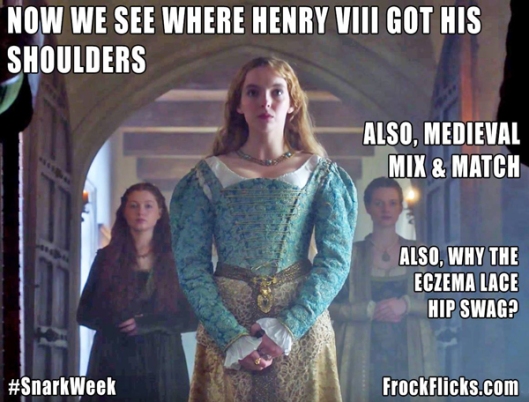

Edgerton as Falstaff

Henry trusts Falstaff so much that by the end of the film, Falstaff is rising to the occasion. When Henry’s forces encounter the French at Agincourt, it’s Falstaff who councils Henry to fight the battle and lays out a strategy that basically involves suckering the French into an ambush. To make the trick work, Falstaff volunteers to lead a small force of Henry’s knights into battle, tricking the French into thinking that they have a much greater numerical advantage than they do. Falstaff does this knowing that there’s a good chance he will be killed, and in fact he does die in the battle. So rather than an unheroic off-stage death that is merited by Falstaff’s essentially parasitical nature, Edgerton’s Falstaff dies a profoundly heroic death, having been redeemed by Henry’s faith in him.

That obviously differs dramatically from Shakespeare, but an even bigger problem is that Falstaff is a fictitious character and therefore cannot have played any role in the historical battle of Agincourt.

Shakespeare’s Falstaff is very loosely inspired by the historical Sir John Oldcastle. Oldcastle had served Henry IV and eventually became involved in the fight against Glendwr, which brought him into contact with Young Henry. This proved to be a very advantageous connection for Oldcastle; he was brought into the prince’s household and began receiving various marks of royal favor, eventually being able to marry a very wealthy widow of the high nobility.

But by 1410, Oldcastle had become quite sympathetic to the Lollards, a heretical movement that argued against the need for priests (to be very simplistic about it). Archbishop Arundel of Canterbury, who was extremely concerned about the threat of Lollardy, found hard evidence that Oldcastle was a supporter of the movement. Arundel showed the evidence to Young Henry, who summoned Oldcastle to meet with him. Initially Oldcastle was able to persuade Henry that he was innocent, but then he fled and ignored Arundel’s attempts to force him to appear in court. Oldcastle finally appeared, was convicted as a heretic, and sent to the Tower of London.

Oldcastle escaped from the Tower and plotted a coup in which the monarchy would be replaced with some other sort of government, the monasteries would be dissolved, and a few other improbable things were planned. A group of Lollards actually tried to put the plan into motion, but Prince Henry got word of it and they were all arrested, except Oldcastle, who managed to elude capture for four years. He was captured and executed in 1417.

A 16th century illustration of Oldcastle’s execution

Notice that Oldcastle and Falstaff are quite different. They’re both knights and friends of Prince Henry, and they both wind up getting repudiated by him eventually. But Falstaff is not a heretic or a rebel the way Oldcastle was.

However, the scandal around Oldcastle remained famous. In the 1580s, an anonymous London playwright published The Famous Victories of Henry V, in which Henry and ‘Jocky’ Oldcastle are basically robbing people until Henry learns that his father is dying, which causes Henry to mend his ways and banish his old friends, including Jocky. It’s not a great play, but it gave Shakespeare the raw material for the Henriad.

And it’s pretty clear that Shakespeare was thinking of Oldcastle when he wrote the Henriad. In Part 1, Hal refers to Falstaff as “my old lad of the castle,” a pun that would only work if Shakespeare felt the name Oldcastle was still relatively well-known. The epilogue of Part 2, however, contains an explicit statement that Falstaff is not Oldcastle, “for Oldcastle died martyr, and this is not the man.” While all the surviving copies of Part 1 call the character Falstaff, there is reason to think that in its first performances, he was explicitly named Oldcastle. In one of the oldest copies of the text, one of Falstaff’s speeches is accidentally labelled ‘Old.’ rather than ‘Falst.’ and one line of dialog scans improperly with the current reading ‘Falstaff’ but properly if it’s read as ‘Oldcastle’.

It appears that Shakespeare originally used Oldcastle, but then ran into the problem that Oldcastle’s living descendants, the Cobhams, were powerful people who held government office and enjoyed the ear of Queen Elizabeth. So after Henry IV, Part 1 premiered, the Cobhams complained either directly to Shakespeare or to some royal official who made it clear that Shakespeare had to change the play, which he prudently did, and then threw in a disclaimer on Part 2 that any resemblance of Falstaff to anyone living or dead was entirely coincidental. And he capped it by positioning Oldcastle as a Protestant martyr to show he was really serious that Oldcastle was a good guy.

The Worst Part of The King

While the film’s revision of Falstaff as a character is weird and honestly not very interesting, the worst part of the film is the end, because Edgerton or Michôd decided that the film needed a twist ending, because apparently neither history nor Shakespeare got it right the first time. In Henry V, a big part of Henry’s motivation to invade France comes when the king of France insults him by sending him a box of tennis balls, basically suggesting that Henry is just playing a game. In the film, it’s just one tennis ball, but the message is basically the same.

But then his chief justice Gascoigne (Sean Harris) tells Henry that he’s caught an assassin sent by King Charles of France. And then Henry discovers that Lords Cambridge and Grey have been bribed by the French to overthrow Henry. Gascoigne advises Henry to make a show of strength and so Henry executes the two nobles and decides to invade France. In history and in Henry V, the order of events are inverted; the decision to declare war came first.

Harris as Gascoigne

After Agincourt, Henry returned to England with his new bride Princess Catherine (Lily-Rose Depp, demonstrating that nepotism is alive and well in Hollywood). Catherine challenges his motives for invading France and persuades him on no evidence whatsoever that her father would never have sent an insulting gift, or sent an assassin, or orchestrated a coup against him. So Henry questions Gascoigne in a scene that reads like CSI: Eastcheap with Gascoigne proving remarkably inept at covering up his tracks. Gascoigne finally admits that he faked the insult and the assassin and the plot as a way to force Henry to demonstrate his strength, because Gascoigne feels that the only way Henry can achieve unity in England is by proving he can be a strong ruler. Henry stabs him to death and all is well.

This is bad. Way bad. Baaaaad. It views the past like a murder mystery, in which there is a plot to uncover and the story ends once the plot has been revealed and resolved. It positions an entire phase of the Hundred Years’ War as being caused by one man’s decision that Henry needs to show he’s a big boy now. It’s like writing a film in which Octavian tricks Brutus into assassinating Julius Caesar so that Octavian can seize power in Rome. It’s like writing a film in which Ulysses S. Grant tricks the South into seceding as a way to save Grant’s career. It’s like writing a film in which Thomas Cromwell throws Anne Boleyn at Henry VIII in order to trigger the Protestant Reformation (oh, wait, that’s kinda sorta what happened).

Ugh. I cannot easily describe just how shitty the ending of this movie is.

Want to Know More?

Don’t watch The King on Netflix. It’s really not worth it. Watch Kenneth Branagh’s adaptation of Henry V, which is a vastly superior film in all respects.

If you want to know more about Henry V, check out Christopher Allmand’s Henry V.