Tags

Alexander the Great, Ancient Greece, Colin Farrell, Hephaestion, Homosexuality, Jared Leto, Oliver Stone

One of the more controversial elements of Alexander (2004, dir. Oliver Stone) when it came out was the film’s suggestion that Alexander was homosexual. A group of Greek lawyers actually threatened to sue Stone over the issue, and the theatrical cut of the film largely avoided the issue (so far as I can recall, at any rate). But in the Ultimate Cut that Stone released in 2012, Alexander (Colin Farrell) is shown being attracted to men.

In the film Alexander has a favorite male slave, Bagoas (Francisco Bosch), who is presented as sharing his bed. At one point, Alexander gets into bed, and Bagoas climbs in with him and they kiss. On Alexander’s wedding night, when Alexander beds her, Bagoas briefly enters the room, sees that there is someone else in the bed, and discretely leaves. In another scene, Bagoas dances publicly for Alexander in a rather sexual fashion, and Alexander kisses him. So the film pretty clearly shows Alexander as having a male concubine.

Alexander kissing Bagoas

More significantly, his relationship with Hephaestion (Jared Leto) is shown as being more than platonic, although the two men are not directly shown having sex. In one scene, when they are being tutored by Aristotle (Christopher Plummer) as boys, Aristotle starts to talk about Achilles and Patroclus. Hephaestion gives Alexander a pointed looked and asks if Achilles’ love for Patroclus was corrupting. Aristotle replies that when two men lie together in lust, it does nothing for their excellence, but when two men lie together in love, it is a pure thing. On Alexander’s wedding night, Hephaestion gives Alexander a ring and the two men embrace. Roxane walks in and gets upset, asking if her husband loves Hephaestion. Alexander replies that there are many ways to love someone, and then has rather violent sex with her. When Hephaestion dies, Alexander goes crazy and either intentionally tries to get himself poisoned or goes on a bender and falls fatally ill. As he is dying, he holds up Hephaestion’s ring. So while the film isn’t explicit, it seems pretty obvious to me that Stone wants viewers to connect the dots.

Hephaestion longing for Alexander

So, was Alexander the Great gay?

Homosexuality in Ancient Greece

First, we have to acknowledge that the ancient Greeks had no concept of ‘sexual orientation’ or the like. They had no idea that most people are only attracted to the opposite sex but that some are attracted to the same sex or to both. Instead, the ancient Greeks seem to have looked at the choice of sex partners as a matter of taste, mood, and intention. They understood that many men occasionally had sex with other men or with teenage boys, but this did not mean these men did not also have sex with women. A man could easily have a wife or concubine and a boyfriend. Such attractions were to some extent treated as an issue of taste, the way a modern man might say he prefers blondes over brunettes, or say that he’s a ‘legs man’ or a ‘boobs man’. Some authors such as Plato argued that the most meaningful forms of love could only occur between men, and that real love could not exist between a man and his wife, in part because she was likely to be uneducated and therefore could not act as an emotional companion.

When the Greeks spoke about same-sex attractions, they most commonly did so through the lens of the erastes-eromenos relationship. The erastes was an older, married man (so, at least in concept, a man in his later 20s or older) who gave affection to his eromenos; he was the ‘lover’. The eromenos, or ‘beloved’, was a younger male, somewhere between early teens to early 20s, who was the recipient of affection. The erastes was both a sexual lover and a mentor to the eromenos, someone who helped usher him into adult male society through socialization. Whereas modern Americans view one of the father’s duties as teaching his sons ‘how to be men’, the ancient Greeks felt that this duty belonged at least in part to the erastes.

An erastes kissing his eromenos

But this was a complex relationship, because in the Greek world, sex was an expression of power relationships at least as much as it was an expression of romantic feelings. A man was expected to have sex with those who were beneath him socially. His wife was beneath him because she was a woman. His slaves were beneath him because they were his property. Male and female prostitutes were beneath him because they were lower class. And his eromenos was beneath him because the eromenos was not a full adult. But the eromenos would eventually reach adulthood and become a full citizen. This made homosexual sex an awkward issue for the Greeks, because it was acceptable for a teen or young men to be sexually receptive, but a fully adult man was expected to only be sexually active. Ok, let’s be blunt, an adult man had to be the penetrative partner. To be penetrated was perceived to be unmanly. It was socially awkward for an adult man to have been sexually penetrated when he was younger, because it raised questions about his masculinity as a full adult.

So the Greeks generally avoided talking directly about exactly what happened when an erastes got busy with his eromenos; looking too closely at that made them anxious. Consequently, many earlier scholars insisted either that this was a non-sexual relationship or that it involved non-penetrative forms of sex such as frottage (which is scholar-speak for dry humping).

In theory, Greek men only had sex with younger, unmarried men. But in practice, things were probably more complicated than that. We also know that the Thebans and the Spartans expected their soldiers to form romantic and sexual relationships, because they would fight harder to impress their partners and to keep them alive. The elite Theban troops, the Sacred Band, were comprised of such partners. And modern homosexual relationships often involve an older and a younger adult partner; ‘daddies’ and their ‘boys’ are both full adults, but the older man takes a leadership role in the relationship. This suggests to me (and I think to other gay scholars who have considered this) that the eromenos may not always have been a literal ‘boy’, but merely a younger man. In other words, two adult Greek men may well have had a sexual relationship, despite the fact that such a relationship would violate the cultural norm.

Far from being a shadowy thing, same-sex love was celebrated as a cultural ideal that even the great heroes and the gods engaged in. Zeus kidnapped the mortal ‘boy’ Ganymede to be his immortal eromenos, and Apollo pursued Hyacinthus for the same reason. In fact, every major Greek god other than Ares is described as having a male lover. The greatest warrior in Greek literature, Achilles, famously fights to avenge his dead companion Patroclus in The Iliad. Homer never explicitly describes the men as lovers, but by the Classical era in Greek culture (roughly, 510-323 BC), the two men were understood be erastes and eromenos, although there was a debate about which role was played by which man.

In this image of Achilles tending the wounded Patroclus, the artist has depicted Achilles as the eromenos (the beardless one)

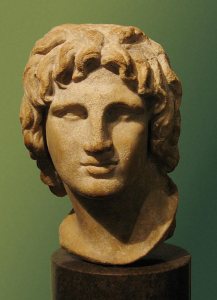

Alexander

So what about Alexander? We know that he married three women, the Bactrian noblewoman Roxane, supposedly out of love, and the Persian princesses Stateria and Parysatis, supposedly for political reasons. Roxane gave him a son and miscarried a second child, so clearly they were having sex. He also had a son by a concubine Barsine. So it is clear that if he was attracted to men, it was not so strongly that he didn’t also have sex with at least two women. Thus in modern terms, he was not gay, but may have been bisexual.

His relationship with Bagoas is not well-detailed. Plutarch tells us that Bagoas won a dancing competition before Alexander, and the troops urged Alexander to kiss him, and another author describes Alexander as kissing Bagoas very passionately, to the applause of the troops. But whether he became Alexander’s concubine is unknown; that’s a modern idea largely created by Mary Renault in her novel The Persian Boy. (See Correction below)

Alexander’s relationship with Hephaestion is more complicated to figure out. It is clear that the two of them were extremely close throughout their lives. Several ancient authors claim that Alexander described Hephaestion as his alter ego, implying for ancient audiences that the two men enjoyed the deepest friendship possible. But were they more than friends?

Only one ancient author, the philosopher Diogenes of Sinope, explicitly says that the two men were lovers. A letter, supposed written by Diogenes but possibly a forgery, says that Alexander was “ruled by Hephaestion’s thighs.”

Alexander and Hephaestion

However, Arrian tells us that when Alexander first led his army from Greece into Asia Minor, he stopped at Troy, where he laid a wreath at Achilles’ tomb and Hephaestion did the same at Patroclus’ tomb. The symbolism of that gesture is powerful and a strong suggestion that they saw themselves as having the same kind of relationship. If that’s true, then they were lovers.

If that’s the case, why don’t any ancient authors explicitly say the men were lovers? One possible answer is that there was the same uncertainty about them as about Achilles and Patroclus. Which one of them was the erastes? Alexander was undoubtedly the higher status man, which means he ought to have been the lover, but Diogenes’ accusation carries the suggestion that Alexander was not the one in charge of the relationship. The idea that the greatest conqueror in the ancient world might have been the one getting penetrated would have been as shocking as it would be for a modern action hero in a film to be getting penetrated. But while Hephaestion was socially the inferior partner, he was still a full adult and a very important man, so he could not have been the receptive partner either. So perhaps ancient authors discretely passed over this question by simply talking about an intimate friendship and assuming the reader would draw the fairly obvious conclusion.

There’s no slam-dunk proof that Alexander carpe’d the diem with Hephaestion. Given the evidence, I think it makes sense to assume that he did, and that in modern terms he was bisexual. But it’s possible that he was, in modern terms, straight and merely enjoyed a very close friendship with Hephaestion. The gay community wants to reclaim as much of its history as possible, and having one of the greatest conquerors in world history in our camp carries considerable symbolism, as those Greek lawyers understood. But wanting Alexander to be gay is not proof that he actually was, and we’ll probably just have to accept that, as with so many other details of his personality, we can’t completely resolve the issue.

Correction: It’s been pointed out to me that there is some ancient authority for the claim that Bagoas was Alexander’s concubine. The 1st century AD Roman historian Curtius Rufus reports that Bagoas had a sexual relationship with Alexander and that Bagoas wielded a certain amount of power at court as a result of it. Curtius Rufus’ sources aren’t known for certain, but he may have been using Cleitarchus’ and Ptolemy’s accounts in his history. Regardless of how factually accurate his claims are (and I see no obvious reason to reject them), it’s clear that Mary Renault was not the creator of this idea, although she’s probably the popularizer of it.

Want to Know More?

Amazon doesn’t carry the Ultimate Cut, but does carry Alexander, Revisited: The Final Cut (Two-Disc Special Edition). Stone based his film on Robin Lane Fox’s Alexander the Great. Fox is a well-regarded ancient historian, but at almost 600 pages, reading it is a serious commitment. If you want something a bit shorter (and more recent), I liked Ian Worthington’s Alexander the Great: Man and God

. If you want to dig a bit deeper into Alexander, you might start with Alexander the Great: A Reader

. And if you want to read one of the original sources, start with Arrian’s account, available as The Campaigns of Alexander (Classics)

.