Tags

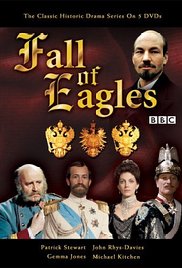

20th Century Europe, BBC, Communism, Fall of Eagles, Julius Martov, Karl Marx, Lenin, Patrick Stewart, Vera Zasulich

The one 19th century ideology that Fall of Eagles addresses head-on is Socialism, or more properly the subset of Socialism that is Communism, obviously because it played such a huge role in the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty in Russia. So the series focuses on the Communists in two episodes, “Absolute Beginners” (episode 6) and “The Secret War” (episode 12). The former deals with Vladimir Lenin maneuvering to take control of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, while the latter sees Lenin and his followers smuggled into Russia during the Great War.

Marx and Engels had developed the basics of Communist theory in the 1840s. In Marx’ view, history was driven by a process of class struggle. In various societies, the details differed, but there were always two social classes, an upper dominant class and a lower class oppressed by the upper class. Eventually the two classes would come into direct conflict and the upper class would make conditions for the lower class so oppressive that the lower class would revolt and overthrow the upper class. Then the lower class would restructure society with itself as the new upper class, while a new oppressed lower class would eventually emerge from the selfish actions of the new upper class. This cycle of oppression, overthrow, and restructuring was, for Marx, the engine of all historical change.

As Marx saw it, the French Revolution had put the ‘bourgeoisie’ on top, by which he meant the class of men who owned the factories, mines, railways, banks, and other elements of capitalist manufacturing. They controlled all the elements of industrial production except for the labor to run the mines and factories. The labor was provided by the ‘proletariat’, the manual workers, who were being horrifically oppressed by the brutal working conditions in 19th century factories and mines (child labor, excessive hours, low wages, dangerous working conditions, and so on). Communist theory primarily makes sense in the context of the Industrial Revolution, which by the 1840s was in full swing across Western Europe.

Marx predicted that the next cycle of revolution would involve the proletariat rising up and overthrowing the bourgeoisie. They would seize control of the state, which would take over the running of the factories on behalf of the workers. Essentially, the workers would be running the factories they worked in. Because of that, the factories would no longer be oppressive to the workers, and because the workers were not oppressing themselves, there would be no new lower class. Thus the cycle of class struggle that had driven society since the beginning of history would come to an end because a classless society would be created.

Karl Marx

So much for the basic principles of Communist thought. For Lenin and his fellow Russian Communists, the big debate was how to apply this model to Russia, where the country just barely beginning the Industrial Revolution. The country’s economy was overwhelming agrarian in nature, with only a small number of extremely brutal factories having been established by 1900. Without the Industrial Revolution and an industrial proletariat, how could the Proletarian Revolution occur? Since Marx’ ideas were understood by his followers to be scientific the way that Newton’s Laws of Gravity were scientific, it appeared to many Russian Communists that things would have to get worse before they could get better; the Russian bourgeoisie would have to be encouraged to seize control of the Russian state and spread the brutality of the Industrial Revolution before there was a large enough proletariat to achieve the Proletarian Revolution. Ultimately, Lenin came to disagree with that view, arguing that it was possible to leapfrog the Industrial Revolution and achieve the Proletarian Revolution in a largely peasant society. His modification of Marx and Engel’s theories came to be called Leninism.

But the RSDLP was more than just Lenin, and many other Russian Communists had different ideas. Lenin’s chief position of influence in 1900 was as a member of the board of the RSDLP’s newspaper Iskra (‘Spark’), which was published somewhat sporadically because Lenin had to keep relocating because of pressure from various governments. By 1902, Lenin and Iskra was based in London, with an editorial staff that included Lenin, Julius Martov, Georgi Plekhanov, Vera Zasulich, and later Leon Trotsky. In 1903, this group was able to convene the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP, first in Belgium and, when that meeting was broken up by the Belgian police, then in London.

Lenin

In London, a rift opened within Iskra’s board. In a debate over how to define ‘party member’, Lenin pushed for a definition in which a party member was a member of one of the party’s recognized organizations (and therefore under the party’s control), whereas Martov advocated for a somewhat looser definition of any person who was working under the guidance of the party (but not necessarily a formal member of any organization). While the difference was small, it represented something quite large. Lenin had a vision of a party of professional revolutionaries who were financially dedicated to the party with a large penumbra of less committed sympathizers, whereas Martov wanted a more broadly-based group of activists who were all moving in the same general direction but not necessarily completely in unison with the RSDLP’s theories. Lenin’s position allowed for the existence of a class-like group of guiding intellectuals, whereas Martov represented a more traditionally Marxist classless system. When the issue came to a vote, Martov’s position won out by a slim majority of 5 votes (out of a total of 51). But 7 of Martov’s supporters later walked out, mostly over the question of how to handle Jewish members (should they be grouped together as the Bund, their own branch of the party, or not?), giving Lenin the majority of 2 votes that he needed to establish his definition of party member.

This led to a rift between Lenin and Martov, who was backed by Zasulich, Trotsky, and eventually Plekhanov. Lenin ultimately labeled Martov’s faction the Mensheviks (‘the Minority’) and his faction the Bolsheviks (‘the Majority’), despite the fact that neither side had a consistent dominance over the party. However, when Lenin’s attempt to restrict the editorial board of Iskra to just three (himself, Lenin, and Plehanov) was defeated, Lenin left the paper, giving it over to the control of the Mensheviks.

Lenin in Fall of Eagles

Patrick Stewart is perfectly cast as the aggressively determined Lenin (more than a little of his later performances as Captain Picard shine through). Not only does he look a startling amount like Lenin, he perfectly captures the man’s moral certainty. “Absolute Beginners” focus closely on the debates around Iskra and the 2nd Party Congress, so the episode appears set in 1903.

Stewart as Lenin

The episode doesn’t delve very deeply into the Marxist ideas at the root of the Communists’ goals. Perhaps the author assumed that the viewers already understand basic Marxist theory. Instead, we get a debate between Lenin and Zasulich (Mary Wimbush) over the question of whether the Russian peasantry can be combined with the proletariat or not. As Zasulich points out sarcastically, the peasantry will have to be involved in the revolution because there are too many of them for Lenin to massacre, but Lenin dogmatically insists that only the proletariat can be involved in leading the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Then an ugly incident occurs in which a messenger arrives with word about a party member, Nikolay Bauman. Bauman had gotten a married party member pregnant and then began spreading malicious rumors about her (which included a vicious satirical cartoon of her as a pregnant Virgin Mary). The woman committed suicide. Martov (Edward Wilson) is very upset about the incident, but Lenin refuses to even meet with the messenger because Bauman was a good party worker, which in Lenin’s mind means that they should overlook his “personal misdemeanor’. Zasulich is disgusted by Lenin’s decision and storms out. The episode presents this as the thing that triggered Martov’s eventual falling out with Lenin.

Wimbush as Zasulich

The Bauman incident certainly came to be seen as an ethical distinction between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks, but moreso after the rift had occurred than as a cause of it. But the episode is very hostile to Lenin. He is depicted as hard and doctrinaire and essentially power-hungry; at one point, he has a fever dream in which he repeatedly says “I am the party!” When he learns that Martov has gone to Geneva to meet with Plekhanov (Paul Eddington), Lenin immediately suspects that Martov is maneuvering to betray him, so he goes to Geneva and plots with Plekhanov to seize control of the party.

The episode then devotes a full 15 minutes to the debate over the definition of ‘party member’ at the 2nd Congress. Martov and Lenin lay out their differences quite clearly and Martov wins. It’s clear that Martov still regards Lenin as a friend and tries to soothe over their differences, but Lenin clearly regards him as an enemy. He manipulates matters to offend the Jewish delegates in order to get them to walk out (and blatantly locks Martov out of a key meeting in order to achieve that). He accuses Martov of betraying his principles in a scheme to achieve control, when in reality it’s clear that Lenin is the one who’s angling for power. He uses Martov’s desire to patch up their friendship to force Martov to denounce the Jewish Bund, leading to the walkout by the Jewish delegates. The impact of the walkout on the voting is never explained, so the emphasis here is mostly on Lenin being a dick to his former friends.

Then Lenin proposes reducing the Iskra board to himself, Plekhanov, and Martov, prompting Zasulich to denounce him and walk out, leading with her several more delegates. Martov rejects his nomination, having realized that Lenin is a vicious schemer. Trotsky (Michael Kitchen) also denounces him and walks out, while Lenin sits impassively watching the responses. By the end of the episode, Lenin is convinced of his own righteousness, but has alienated almost all of his previous friends.

Wilson as Martov

While this portrait of Lenin is not false, it is perhaps incomplete. It makes no attempt to show why Lenin was able to inspire such devotion among his followers, and his persuasiveness appears to be purely intellectual, not driven by his intense charisma. Stewart’s Lenin is not so much charismatic as overbearing, and it’s unclear why his wife Nadezhna (Lynn Farleigh) stays with him after he destroys Zasulich. In reality, he was deeply devoted to her, and passionately fond of children. (His love of children actually became an element of later Soviet propaganda.) But these more positive traits would detract from the view of Lenin the show is offering, and so they are disregarded. This is perhaps an artifact that Fall of Eagles was made during the Cold War, when Western culture had to cast Soviet figures in a negative light.

This is my last post on Fall of Eagles. I’d like to thank my reader Stephen for pointing me toward this series, which I’d never heard of before. Hopefully you feel like you got your money’s worth from these reviews. If there’s a film or tv show you’d like me to review, please consider making a donation to my Paypal account; if I can track it down and think it’s appropriate for the blog, I’ll give it a review.

Want to Know More?

Fall of Eagles is available on Youtube. The series is available through Amazon, but if you decide to buy it, make sure you’re getting a format that will play on your DVD player; some versions only play British and European formats.

If you’re interested in Lenin, one of the best biographies of him is by Robert Service, Lenin: A Biography.

It’s sometimes criticized for its scholarly focus on small details, so if you want something a bit lighter, you might try Catherine Merridale’s Lenin on the Train, which deals with his role in the Great War and his fateful train journey into Russia in 1917.