Tags

Agora, Alejandro Amenábar, Alexandria, Ancient Egypt, Ancient Rome, Christianity, Hypatia of Alexandria, Movies I Love, Parabalani, Rachel Weisz, Roman Empire, St Cyril of Alexandria

One of the central themes in Agora (2009, dir. Alejandro Amenábar) is religious conflict. The film’s prologue text tells us “The Library [of Alexandria] was not only a cultural symbol, but also a religious one, a place where the pagans worshipped their ancestral gods. The city’s long-established pagan cult was now challenged by the Jewish faith and a rapidly spreading religion until recently banned: Christianity.”

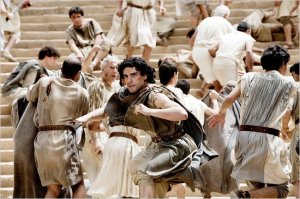

One of the very early scenes in the film takes place in the agora, the marketplace/public square that was the center of any Greek city. We see a Christian monk, Ammonius (Ashraf Barhom) debating with a pagan philosopher over a bed of burning coals. Ammonius demonstrates his faith in Jesus by walking across the bed without getting burned, and then he grabs the philosopher and throws him into the fire, where he is badly burned. This ‘miracle’ plants a seed of faith in the mind of Davus (Max Minghella) that will gradually blossom into a full-blown and violent conversion.

The religious upheaval in Alexandria remains front and center throughout the film. In 391, we see the pagan scholars of the Library attack the Christians for the assault on the philosopher, which turns into a siege when the Christians counter-attack, trapping Hypatia (Rachel Weisz) and Orestes (Oscar Isaac) in the Library. Eventually Emperor Theodosius resolves the problem by ordering the pagans to evacuate the Library and letting the Christians ransack it, destroying all the books in it and tearing down the statue of Serapis. Eventually, it is turned into a Christian church.

The second act opens in 415 and explores the rising tensions between Christians and Jews. Ammonius and Davus sneak into a musical performance that many Jews are attending and break it up by throwing stones. The Jews retaliate by raising a false alarm that one of the churches is on fire, and then trapping a bunch of monks in the church and stoning them to death. This leads to the expulsion of the Jews from Alexandria.

In the third act, Hypatia becomes the focus of the tensions, as Christians begin to suspect that she is the driving force behind Orestes’ conflicts with Patriarch Cyril (Sami Samir). They pressure Orestes to cut off all contact with her, and eventually she is attacked by a mob of Christians and murdered. Her death is presented as a sort of martyrdom to the cause of freedom of thought and intellectual inquiry.

When the film came out, there were complaints by Christian organizations that the film was propagating stereotypes about Catholics as narrowminded, irrational anti-science bigots. It’s easy to see why the critics felt this way—the Christians certainly come off as intolerant, violent thugs with no interest in understanding the physical world.

The Religious Situation in Alexandria

4th century Alexandria was an extremely complex place. It was one of the largest cities in the ancient Mediterranean. It was one of the major centers of pagan worship, and it also housed one of the largest Jewish communities anywhere in the world after the Jewish diaspora. It occupied two of the city’s five quarters (although that doesn’t mean that 40% of the population was Jewish).

Alexandria was also a major center of Christianity from the 1st century AD onward. Legend claims that the Evangelist Mark was one of the founders of the Christian community there, and by the 3rd century the bishop of Alexandria was considered to be one of the five patriarchs of the Christian world (alongside those of Jerusalem, Antioch, Rome, and later one Constantinople). Other bishops looked to the Patriarch of Alexandria for leadership, although the patriarchs had little formal power over other bishops. (The patriarchs were essentially ‘first among equals’, rather than hierarchically above other bishops).

By the end of the 4th century, the Christian community was extremely large, although it’s hard to say if it was the majority of the population or not. In the later 4th century, the shifting religious balance of the Roman Empire created all sorts of religious conflicts in many cities. Christians who had up until the early 4th century been the targets of state persecution began to attack pagans and to a lesser extent Jews, but pagans were still strong enough to fight back. Pagans were unused to having to share political and social power with Christians, and Christians increasingly expressed a sense that pagan temples and festivals were inherent threats to them, temptations to sin, and the like. In that situation, both Christians and pagans could easily become targets of religious aggression. Religious riots were a frequent problem in larger cities. While Christians did not always win the fights, the fact that the emperors were now Christian meant that they usually triumphed at the end of the dispute.

But the Christian community was not a monolithic group. Early Christianity saw many debates over Christology (basically, the theological issue of who exactly Jesus was and is). In the 3rd century, the Alexandrian theologian Origen emphasized the Unity of God in a way that tended to downplay Jesus and treat him as ‘the image of God’, like light radiating from the sun. In the 4th century the most heated controversy was over the question of whether Jesus was an original part of God or whether the Father had created the Son as his first act of creation. This debate first erupted in Alexandria in the early 4th century when Arius of Alexandria (the proponent of the latter position) got into a heated dispute with Athanasius, the Patriarch of Alexandria. In 325, Emperor Constantine convened the Synod of Nicaea, which ultimately sided with Athanasius and declared Arianism a heresy. But it took close to a century for the issue to finally get resolved, because Arius had many supporters, and Arianism continued to find periodic political support in various parts of the Empire.

St Athanasius

Arianism wasn’t the only issue of controversy. 4th century Christians carried about theology the way that modern Americans care about things like the economy, racial issues, gun control, whose football team is better, and whether Batman could defeat Superman. Alexandria was home to the Catechetical School, a theological school that also taught logic, literature, and natural philosophy (the sort of proto-science that Hypatia taught at the Serapeum). This ensured that there was a substantial number of men who cared deeply about learned matters from a Christian perspective and who were willing to engage in theological debate. In fact in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the leading scholars of the Catechetical School were arguably more important than the Patriarchs of Alexandria in terms of their influence. The Novatianists rejected the idea that mortal sins (such as murder or worshipping of pagan gods) could be absolved, a doctrinal stance that put them at odds with most Christian theologians.

The New monasticism

In the 3rd century, Egypt saw the emergence of perhaps the first Christian monastic communities. These earliest monks and nuns were seeking to reject the temptations of their bodies by indulging in acts of extreme asceticism (things like prolonged fasting, sleep deprivation, doing without property, permanent chastity, and so on), through which they hoped to learn to ‘turn off’ the physical desires of their bodies so that they could gain a clearer sense of God’s will.

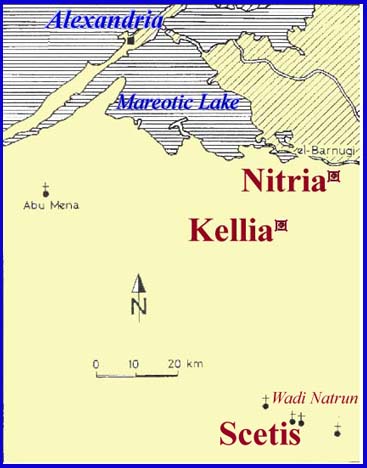

But few of these men were ready to simply go out into the desert all on their own. They recognized that there were a lot of ways that novices could get into spiritual danger. So they tended to gather in communities where the more experienced among them could mentor the novices. One of the major centers of this early monasticism formed at Nitria, quite near to Alexandria. By the 390s, it was a community of thousands, large enough to support merchants and bankers who served the needs of the Nitrian monks. Other major communities developed just slightly further away, at Kellia and Scetis.

Because these monastic communities were so close to Alexandria, it was easy for tourists to come to watch them. And it was easy for the Nitrian monks to get involved in Alexandrian politics. So when controversy was brewing in Alexandria, the Nitrian monks sometimes participated in mob actions.

Alexandria was also home to a group of men called the Parabalani (literally, ‘those who risk their lives as nurses’). This group is very poorly documented but it seems to have been a quasi-monastic organization of men who devoted themselves to caring for the sick and burying the dead. This meant they were exposed to things like infectious diseases, especially during epidemics, and were thus risking their lives as an expression of Christian charity (especially since caring for the sick is one of the 7 Works of Mercy that Christ ordered his followers to perform). They were considered to be members of the clergy, and enjoyed some legal benefits that meant that people sometimes falsely claimed to be members of the group and the wealthy sometimes bought their way into them.

The group seems to have been notoriously disruptive in Alexandria. A law issued probably around 416 declared that there should not be more than 500 Parabalani, that their members should all be poor, and that they not attend public theatrical events or law courts. This was issued “on account of the terror of those who are called ‘parabalani’. “ This suggests that the Parabalani had a tendency to cause trouble at theaters and law courts. In 449, they were accused of bursting into a church and threatening a priest who was quarrelling with the patriarch of Alexandria. So it seems that the patriarchs of Alexandria (or at least the less scrupulous ones) had a tendency to use the Parabalani to bully their opponents into submission.

Turbulence in Alexandria

In 379, the Emperor Theodosius I decided to impose Nicene (Athanasian) Christianity on the entirety of the Empire. He expelled all the Arian clergy from their churches (including in Constantinople, a heavily Arian city). He ordered Demophilus, the Arian Patriarch of Constantinople, to embrace Nicene Christianity or give up his seat; Demophilus chose the latter. Theodosius appointed Gregory of Nazianzus, but another faction tried to sneak in Maximus the Cynic. This group appealed to Patriarch Peter of Alexandria, promising him that Maximus would admit that his patriarchate was inferior to that of Alexandria. But the Constantinopolitan populace was outraged and forced Maximus to retreat from the city. Two years later, Theodosius convened the First Council of Constantinople in an effort to resolve these controversies. After a great deal of wrangling over the question of whether Gregory was qualified to be patriarch, he stepped down, but the Council decreed that the patriarchs of Constantinople had precedence over those of Alexandria, because Constantinople was the New Rome. This ruling so outraged the Alexandrian population that a massive riot engulfed the city, during which the Catechecal School was completely destroyed, never to be rebuilt.

A decade later, in 391, Theodosius issued an order forbidding the public performance of any religious rituals that were not Christian. Patriarch Theophilus of Alexandria took control of a temple of Dionysius and when a subterranean worship space was discovered in it, he mockingly displayed the religious paraphernalia that were found therein. This provoked the pagans of Alexandria to riot over this insult. The Christians eventually counter-attacked, probably with the aid of either the Parabalani or the Nitrian monks, and forced the pagans to retreat into the Serapeum. Theophilus apparently appealed to Emperor Theodosius, who responded by pardoning all the pagans for the riot but giving Theophilus permission to destroy the temple.

Theophilus standing on the temple of Dionysius

But Theophilus was not just hostile to the pagans. He also persecuted the remaining Origenists, reportedly massacring 10,000 Origenist monks (the number is probably exaggerated). In 403, he also helped orchestrate the removal of the patriarch of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, because John was protecting some Origenists and because Theophilus was hoping to reverse the subordination of Alexandria to Constantinople.

When Theophilus died in 412, a riot broke out over the question of who should succeed him, his nephew Cyril or his rival, the archdeacon Timothy. When Cyril’s supporters won, Cyril quickly began persecuting the Novatianists, evicting them from their churches.

More significantly, Cyril began to quarrel with the Christian governor of Egypt, Orestes, who perceived Cyril as trying to encroach on his political authority. In 415, Orestes issued an edict regulating mime shows, which were extremely popular in Alexandria and were frequently the occasion of violence (remember that law dealing with the Parabalani?). Cyril sent Hierax to find out what the edict involved. Hierax approved of the edict and read it aloud in a theater, which provoked the Jewish population, who considered Hierax a troublemaker and suspected him of trying to incite violence. The Jews rioted and to mollify them, Orestes had Hierax publicly tortured, intending to send Cyril a signal about who was really in charge.

Cyril threatened to retaliate against the Jews, which infuriated them even further. They organized a scheme in which they spread word that a Christian church was on fire. When the Christians turned out to save the church, the Jews attacked them, killing many. Cyril responded by expelling a reported 50,000 Jews from the city and allowing the Christians to plunder them as they left.

St Cyril of Alexandria

Both Cyril and Orestes complained about the other to the emperor and Cyril reportedly tried to broker a peace between them, but he seems to have expected Orestes to acknowledge that as a religious leader, Cyril had the superior authority, which Orestes refused to accept. A group of monks (either Parabalani or Nitrians) attacked Orestes and one of them, Ammonius, hit the governor on the head with a rock. In the ensuing brawl, Orestes’ bodyguard fled, but the Alexandrian population intervened to rescue him.

Orestes had Ammonius tortured to death, but Cyril promptly confiscated the corpse and declared the monk a martyr. The Christian population wasn’t convinced, and Cyril eventually had to abandon his attempts to canonize Ammonius. Popular pressure forced the two leaders to reconcile, but both seem to have attempted to get the upper hand. Orestes sought support from Hypatia, who was influential with what remained of the city’s pagan community, while Cyril began claiming that Orestes was abandoning his faith and that Hypatia was seducing him either sexually or with magic.

Eventually, a mob of Christians attacked Hypatia and either dragged her out of her chariot, took her to a church, stripped her naked and then stoned her to death or else dragged her through the streets until she died. Neither of the two descriptions of her death says exactly who did this, saying only that they were Christians led by Peter, who is variously described as a ‘reader’ (a church official) or a ‘magistrate’ (a secular official). Given the violent tendencies of the Parabalani, modern suspicion has tended to fall on them, and since we know that Cyril’s successor as patriarch used them to violently intimidate his opponents, it’s usually suggested that Cyril was behind the killing, either directly or indirectly. It’s certainly a plausible reconstruction from what we know, but it’s going beyond the sources to say either that Cyril ordered it or that the Parabalani were the ones who did it.

Hypatia (Weisz) about to be stoned by the Parabalani

Agora

Agora does a pretty good job of capturing the turbulent nature of Alexandrian politics in the period from 391 to 415. Historically, pagans, Jews, and Christians all took their turns both as instigators and victims of violence, and the film shows this. The sequence it offers of Christians harassing pagans in the marketplace, which grows into an anti-Christian riot until the Parabalani get involved and siege the pagan scholars inside the Serapeum until the emperor orders the destruction of the temple is essentially factual. Where the film takes a liberty is that it emphasizes the destruction of the Serapeum’s library, which is not mentioned in the surviving sources, which instead dwell on the destruction of the pagan idols.

Orestes (Oscar Isaac) rioting against the Christians

Later, the film shows the Parabalani throwing rocks at a theatrical performance, which triggers first a Jewish protest to Orestes, then a Jewish scheme to lure the Parabalani into a church and stone them. That triggers the expulsion of the Jews. Hierax is omitted, as are a few other small details, but the sequence of events is basically true.

Cyril’s attempt to reconcile with Orestes is presented as a power play in which the patriarch puts Orestes on the spot during a church service, reading out 2 Timothy 2: 9-12 (“I also want the women to dress modestly, with decency and propriety, adorning themselves, not with elaborate hairstyles or gold or pearls or expensive clothes, but with good deeds, appropriate for women who profess to worship God. A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet.”). It’s a blatant attack on Hypatia, and when Orestes refuses to kneel before the Bible, he appears to be defying not just Cyril but God. This incident happened, but we don’t know what verses Cyril read out in the church, or that the incident was an attack on Hypatia. Nor do we have any specific reason to think that Cyril was a misogynist, although it would not be surprising if he was.

After that, people mob Orestes as he leaves the church, Ammonius hits Orestes with a rock, and Ammonius is executed. Cyril proclaims him a martyr, and his fellow Parabalani plot to murder Hypatia, despite Davus’ efforts to save her. Davus stabs her to death out of mercy before she can be stoned, but beyond that, Hypatia’s death happens roughly the way one of the sources says it did.

Patriarch Cyril (Sami Samir)

So the film’s narrative is based around a pretty solid core of fact. Some details are left out or simplified, and a few (such as Cyril’s attack on Hypatia during the church service and Davus’ mercy killing) are invented. The parts of the film that focus on the political and religious strife in the city are about 80% accurate and much of what is not accurate is reasonable invention.

However, the film does oversimplify the conflicts. As I noted, the Christians of Alexandria were not a unified group. Theophilius and Cyril orchestrated violence against the Origenist and Novatianists and other Christians whom they felt were religiously in error. In the film, the Christians seem mostly united behind Cyril. Orestes seems to be almost the lone Christian opposed to him. One of Hypatia’s other former students, Bishop Synesius (Rupert Evans) attempts to support Orestes, but ultimately feels compelled to side with Cyril. The incident that starts all the violence, the throwing of a pagan philosopher into bed of burning coals by a group of Parabalani, actually involved two different groups of Christians.

The film also oversimplifies things by making the pagans, including Hypatia, the only people genuinely interested in ‘science’, while making the Christians almost entirely disinterested in the physical world. The one time the Parabalani discuss the issue of astronomy, Davus (who understands the heliocentric theory because he’s heard Hypatia explain it) says that only God knows the answer. That essentially puts the Christians in the situation of believing that the physical world is just a mystery of faith that cannot be understood through reason. But that’s a caricature of what late ancient Christians actually thought. While they wrestled with the question of how to use traditional (that is, pagan) knowledge, they did not necessarily deny the many accomplishments of natural philosophy. The Catechecal School taught many of the same things that would have been taught at the Serapeum. Christian authors were hostile to the parts of ancient learning that seemed to them explicitly polytheistic, but not necessarily to subjects like mathematics and natural philosophy.

I don’t think the film is actively anti-Christian, although it seems likely that Amenábar’s atheism influenced his treatment of the story. But I can understand why some have seen the film as hostile to Christianity. The problem is that historically, the Alexandrian Christians were in fact pretty violent during this period. Cyril is one of the most unpleasant men ever to have been accorded sainthood, and if anything the film goes a little easy on him by omitting some of his machinations against his fellow Christians.

However, the casting decisions do perhaps unintentionally make the Christians seem more villainous than the pagans. Hypatia and Theon are played by two light-skinned British actors (Rachel Weisz and Michael Lonsdale, although Weisz’s family is Jewish), whereas the two main villains of the piece, Ammonius and Cyril are played by more swarthy-skinned Israeli and Israeli-Arab actors (Ashraf Barhom and Sami Samir). Since American audiences are accustomed to seeing Middle Eastern actors in roles like terrorists, this casting choice tends to encourage the audience to read Ammonius and Cyril as villainous even before we understand what they want.

Ammonius (Barhom) and Davus (Minghella)

The depiction of the Parabalani is also probably unfair to them. In one scene, Ammonius shows Davus the pleasure of feeding the poor, and in another scene they are show disposing of the dead (victims of the riots the Parabalani were involved in), but overall the film offers minimal awareness that this group was devoted to charity. Instead, they tend to be shown lounging about waiting for an excuse to be violent, and many of them are shown carrying swords. We have little information about how this group was organized, how they lived, or how much of their time was devoted to charity, but the film draws them in broad strokes and never tries to give the audience an understanding of who the Parabalani were other than violent extremists.

Agora is not a perfect film. As noted, it simplifies and at times oversimplifies things. Its depiction of Hypatia’s research into the heliocentric theory is pure conjecture (although given what we know of her actual interests, it’s not implausible conjecture). It conflates the Serapeum with the Great Library and depicts a single catastrophic destruction of that library when in reality it was more a slow death by many cuts. Its narrative of peaceful pagan science vs violent Christian faith is more simple and tidy than things were in reality. Its depiction of 1st century Roman soldiers in 5th century Alexandria is nonsensical.

But overall, the film approaches its subject with far more respect for the historical facts than most movies. Of its two plotlines, one is basically true while the other is at least respectful of the facts. It delves into a poorly known figure and a moment in time that cinema has rarely (if ever) attempted to depict and manages to provide a reasonable depiction of the events. It treats its audience with respect and manages to explain a complex intellectual puzzle in ways the audience can understand, and it takes as its centerpiece the joy of intellectual inquiry and makes the joy intelligible to non-scholars. I’d rank it as one of the better films on ancient Rome.

This review was paid for by Jerise, who made a donation to my Paypal account. Thanks, Jerise! If there’s a film you would like me to review, please make a generous donation via Paypal and let me know what you’d like me to review. If I can track it down and if I think it’s appropriate, I’ll review it.

Want to Know More?

Agora is available through Amazon.

St Cyril, despite being a rather unpleasant man, was extremely important in the development of early Christianity, and there’s a good deal written about him. Norman Russell’s Cyril of Alexandria would be a good place to start. Russell has also written about Theophilus of Alexandria, Cyril’s predecessor. Taken together, these books would be a good look into the turbulent religious world of Late Roman Alexandria.