Tags

ABC, Ancient Rome, Empire, Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, Movies I Hate, Octavian/Augustus, Roman Republic, Santiago Cabrera, Vincent Regan

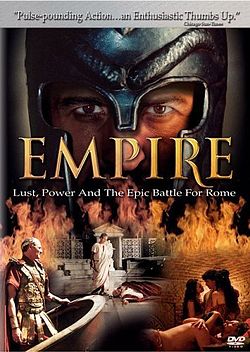

Watching Empire has made me reflect on all the poor life choices that brought me to this moment. If I had decided to study accounting rather than history, I doubt that I would have hit such a bottom watching this wretched ABC mini-series. Still, history only moves in one direction, so I guess I have no choice but to keep going with my review.

The biggest problem with this mini-series is the plot, which lurches around like a bus whose driver is having a seizure, taking out pedestrians, street signs and the occasional parked car before careening off a cliff and exploding in a huge burst of suckage. But in order to explain what is wrong, we need to take a fairly long detour into the actual past.

The Late Republic

By the 2nd century BC, the Roman economy was undergoing significant change, as large numbers of slaves flooded into Italy as a result of Roman victories during the Punic Wars and its slow expansion around the Mediterranean. These slaves forced the value of labor sharply downward and helped force large numbers of citizen farmers off their farms. These displaced farmers tended to do one of two things. Many entered the Roman military, an honorable activity that helped further the expansion of the Empire, which increased the numbers of slaves and perpetuated the forces that were forcing farmers off their land. After a successful military campaign, these men hoped to receive a grant of land in the conquered region, enabling them to return to the ranks of the farmers. But that required someone to enact a specific law granting those soldiers land, and the most logical person to press for that was their general, who used his successful conquest as a stepping stone to high political office. As a result, the military became deeply politicized, with the soldiers viewing their general, rather than the Roman state as a whole, as the natural focus of their loyalty.

The other thing those displaced farmers tended to do was migrate to the cities, especially Rome, in search of employment. But because the growth of slavery had forced down the value of work, most fell into severe poverty, and so Rome developed large slums. Although these men were poor, they could do two things. They could riot, thereby destabilizing Roman politics in unpredictable ways, and they could vote.

These changes caused the development of two new political factions (too loosely-structured to be political parties). One faction, the Optimates or ‘best men’, were traditionalists who appealed to those who were uneasy with the changes taking place. They championed the traditional center of Roman government, the Senate and the consuls, and targeted their political appeal at the aristocratic elites. The other faction, the Populares or ‘men of the people’, were aristocrats who sought political support among the large crowd urban poor, who had emerged as a new factor in Roman politics. They championed the Tribunate, essentially a second parallel branch of Roman government that possessed many (though not all) of the powers of the consuls and who were traditionally much more responsive to the will of the general population. They promised various reforms designed to please the crowd, such as redistribution of land, the distribution of subsidized grain (perhaps the first welfare measure in Western history), and free entertainment in the form of gladiatorial games and other sports. While the Optimates emphasized tradition and the Populares invokes the rights of the people, both groups were essentially ambitious politicians seeking to advance their own power.

Starting in 133 BC, the conflict between these two factions gradually tore the Republican system to shreds. Over the course of the next century, civil war became a regular problem, as ambitious generals used their armies to pursue political victory through military conflict. Assassinations, conspiracies, judicial murders and political purges, and the wholesale violation of the legal framework for politics left Rome at the mercy of whichever faction could achieve temporary dominance.

Finally, in 48 BC, Julius Caesar, the leading Popularis of his generation, defeated the last great leader of the Optimates, Pompey the Great. This left him the unchallenged politician at Rome, and he immediately set about establish political dominance. The Senate was forced to declare him Dictator in Perpetuity, essentially giving him a higher political power than anyone else, using an office that was supposed to be used only in times of crisis and which theoretically had a term limit of 6 months. Normally, the Senate would debate an issue and then give the consuls a recommendation for the consul to issue a law. But Caesar would announce an issue to the Senate, skip the debate, and just issue laws. He repeatedly made clear that he felt no respect for the Senate, and his actions, including accepting deification, strongly suggested that he intended to overthrow the Republican system entirely and establish a new monarchy.

A coin of Julius Caesar

Many of the last remaining Optimates joined with some of Caesar’s closest friends who were troubled by the direction he was taken, and formed a conspiracy to murder him. This group was led by Gaius Cassius Longinus, Decimus Junius Brutus, and his more famous relative, Marcus Junius Brutus (the guy everyone refers to as ‘Brutus’; I’ll call the less-famous one Decimus). These men considered Caesar to be a tyrant who was oppressing Rome and therefore called themselves the Liberators, determined to restore freedom to Rome.

On March 15, 44 BC, a group of about 40 men stabbed Caesar to death in the Senate house. They were in such a frenzy that several of them wounded each other in the process. The rest of the Senate fled in panic, and Brutus marched to the Capitol, declaring that he had liberated Rome. But he and the other Liberators, who had expected to receive a hero’s welcome, were shocked by the hostile reception. As aristocrats who feared being closed out of political power, they had failed to realize just how popular Caesar was with the Roman crowd. As rumors began to spread about what had happened, many Romans barricaded themselves in their houses.

Marcus Antonius, Caesar’s right-hand man, had been slowly drifting away from Caesar for a while, but seized on this opportunity to grab at the reins of power. He negotiated with the Senate and conceded an amnesty to Caesar’s killers, but at the price of their legitimizing all of Caesar’s decrees and appointments. As the crowd became angry, the Senate fearfully voted to declare Caesar a god in an effort to appease them. Brutus gave a speech denouncing Caesar as a tyrant, and for a moment, it seemed that the crowd might be mollified.

Marcus Junius Brutus

But then Caesar’s will was read out. It did three things. 1) It named his grand-nephew Octavius as the heir to his vast fortune and adopted him. 2) It named Decimus as the alternative heir if Octavius was dead. 3) It granted every male citizen in Rome a modest cash gift. (The fact that Caesar could afford to do that and still leave his heir the richest man in Rome demonstrates just how staggeringly rich he was.) These three points all mattered. The first point made it clear that Antonius was not the unchallengable successor to Caesar’s position. The second point made Decimus’ participation in Caesar’s death an impious patricide. The third point reminded the crowd of Caesar’s past gestures to them, which tipped the balance against Brutus’ denunciation of Caesar.

Violence erupted. The Senate house was burned and an unfortunate tribune, mistaken for one of the Liberators, was torn to pieces in the streets. The Liberators fled Rome and Cassius and Brutus seized control of the Eastern Mediterranean portions of the Empire, raising legions for what became a renewed civil war, the Liberators’ War.

Back in Rome, Antonius made common cause with Octavian and Caesar’s cavalry general, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, forming the Second Triumvirate, to which the Senate cravenly turned over complete control of the government. Antony married Octavian’s sister, Octavia. To secure control of Italy, they enacted a brutal purge, the most notable victim of which was the great orator Cicero, Antonius’ personal enemy, whose head and hands were cut off and displayed publicly in Rome.

In 42 BC, the two sides clashed at Philippi in Greece, in two battles about three weeks apart. The Triumvirs won both battles; after the first Cassius committed suicide and after the second, Brutus did so as well. This battle is essentially the end of the Optimates as a group with any meaningful power in Rome.

A coin issued by Cassius, celebrating Liberty

As a result of their victory, the Triumvirs divided the Empire into thirds and ruled as dictators. In 36 BC, Lepidus and Octavian quarreled, Octavian got the upper hand, and forced Lepidus into domestic exile. Meanwhile, Antony had taken up with Caesar’s ex-girlfriend Cleopatra. He repudiated his marriage to Octavia and married Cleopatra, which triggered the final falling out with Octavian and the last civil war of the Republican period. In 31 BC, Octavian’s forces defeated Antony and Cleopatra at Actium and they both committed suicide, leaving Octavian the undisputed master of the Roman world.

Meanwhile, in Bizarro Land

In theory, this is the story Empire is telling, but any resemblance to historical facts is entirely coincidental. At the start of the series, Caesar (Colm Feore) is the dominant man in Rome, but there’s no mention of the civil war with Pompey or the fact that he’s a perpetual dictator who just runs roughshod over everyone else. The Optimates/Populares rift is reduced to ‘everyone likes Caesar except the Senate.’ which is mostly just Cassius (Michael Maloney) and Brutus (James Frain). Caesar has some sort of formal position, but he’s not a dictator, and it’s not clear what his position is, except that his title is apparently ‘Caesar’ (which is at least a half-century too early for it to function as a title instead of just a family name).

Brutus and Cassius assassinate Caesar in order to restore the Republic from Caesar’s domination, but the show bizarrely presents this as a terrible thing, because Caesar loves the people and isn’t doing anything for himself and instead is doing everything for the people. Early in the first episode, Cassius sniffs that Caesar wants to make himself a king and a god, but it’s already clear that Cassius is an envious jerk, so the show explicitly positions the Republic as a bad thing that apparently involves the Senate running things, while the dictator Caesar is positioned as the defender of democracy.

Caesar’s life and death have been read for centuries as a cautionary tale. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar can be read as a warning against overweening ambition, while ever since the American and French Revolution, his story has been seen as a warning about how Republics succumb to tyranny. So the miniseries’ treatment of the material is startling in the nakedness of its anti-democratic stance.

Once you get beyond that, you realize that the show has no idea how Roman government actually worked. The Senate seems to be in charge, but never actually does anything, and I suspect the show thinks that people got elected directly to the Senate, rather than entering the Senate for life after being elected to almost any other public office; Caesar at one point comments that he “used to be in the Senate.” There are two consuls appointed after Caesar’s murder, Hirtius and Panza (which is actually historically correct), but they barely have any dialog and are only seen again toward the end of the series when Mark Antony (Vincent Regan) executes them for no apparent reason except to be evil. The Vestal ‘Order’ (‘college’ would be a more appropriate term) is described as having great political power but being studiously neutral until Camane (a horribly wasted Emily Blunt) decides to use their resources to duplicate Caesar’s will so everyone will know that Octavius (Santiago Cabrera) is the rightful successor. The Senate has no soldiers of its own and has to make due by hiring gladiators, while various senators seem to own their legions.

You don’t pin a toga, you idiot!

Despite not having any troops, and despite everyone in the city hating them after Caesar’s murder, Brutus and Cassius somehow are in complete control of the city, enough so that Octavius, Tyrranus (Jonathan Cake), and Mark Antony have to flee Rome in danger of their lives and ride around trying unsuccessfully to find military allies. But later, Antony has enough soldiers to be back in the city bargaining with the Senate. He and Octavius sign a document making each other their heirs, and then he massacres all his guests at an orgy by dropping asps and wolves on them. And because of Octavius is out of the way, Mark Antony gets to be…Caesar? Something like that.

With Octavius seemingly gone from the scene, Mark Antony wastes no time in going insane and taking power. He exiles Brutus and Cassius from the city as a way to prevent Brutus from committing suicide and becoming “a martyr for Rome”. Leaving aside the fact that martyrdom was a Christian concept and there won’t be any Christians in Rome for more than half a century, exiling someone to stop them from committing suicide makes no sense whatever. Cassius comments, “we should be in Syria raising an army.” Yes, Cassius, you should be, because that’s what you actually did. But after that Brutus and Cassius mostly just disappear from the series. Not only does it make no sense logically or historically, but also it’s feeble scriptwriting to set up Brutus and Cassius as major villains and then simply hand-wave them away so the plot can focus on the struggle between Octavius and Antony. There’s no Liberators’ War or battle of Philippi, just the plot forgetting about them.

Antony and Octavian in front of bust of Caesar that looks nothing like Colm Feore

Octavius survives the poisoning because Camane does a blood-letting on his jugular vein with the help of Marcus Agrippa (Chris Egan). Normally it’s done at the wrist, Camane. Meanwhile Antony has inexplicably made Tyrannus a centurion in his army, where Tyrannus immediately starts pissing off General Rapax (Graham McTavish) by trying to be nice to the soldiers. And for no reason, Antony doesn’t have Cicero killed.

Octavian reads a story of Caesar’s ‘legendary’ 3rd Legion that was lost at the Battle of Bibracte in Gaul. He rides off to Gaul and stumbles into The Eagle of the Ninth, learning that the lost legion has somehow just been living in Gaul for the past decade without anyone noticing. So he persuades the remnants of the 3rd Legion to fight for him by letting them carve a trident into his shoulder-blade and then leads them against Antony at the Battle of Mutina, at which Tyrannus decides to switch sides and helps save the day and Octavius defeats Antony and inexplicably grants him his life, which somehow causes him the win the day and resolve the whole conflict, and then rainbows and unicorns fly out of his ass and everyone lives happily every after, because the Republic is going to get overthrown after all and Octavius gets to be the new dictator and take away everyone’s politial rights.

God I hate this miniseries.

Want to Know More?

If after all this, you inexplicably want to see this steaming pile of crap, you can find Empire on Amazon.

There are lots of biographies of Augustus. The one I have on my shelf is Pat Southern’s Augustus.

Very funny, all this ranting against Empire. LOL sometimes. Keep it up, Andrew.

LikeLike

Thank you. That makes my suffering worth it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I photoshopped pupils in the eyes of Brutus’ bust; he turned out to be a nasty guy with a weak mouth. Wanna see? I can mail you the picture…

LikeLike

Lol

LikeLike

I don’t think I can send pictures in these comments. If you give me your common mail address I send it through there.

LikeLike

This probably won’t surprise you but I looked through the IMDB credits for “Empire”. While it had a script consultant and two script supervisors, the one credit I did not see was historical consultant or historical supervisor.

LikeLike

Pingback: Empire: The Battle of Mutina | An Historian Goes to the Movies