Tags

19th Century England, 19th Century Scotland, Billy Connolly, John Brown, Judi Dench, Mrs Brown, Queen Victoria

The general public never seems to tire of films about European royalty, and I’ve reviewed one or two (or three or four) of them. So let’s tackle another, shall we?

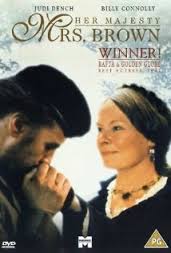

Mrs. Brown (aka Her Majesty, Mrs Brown, 1997, dir. John Madden) tells the story of the unlikely friendship that developed between the widowed Queen Victoria (Judi Dench) and her manservant John Brown (Billy Connolly). In 1861, Victoria’s husband Prince Albert died prematurely at the age of 42 from an attack of typhoid fever. Albert’s death was a terrible blow to Victoria, who loved him passionately, and she went into a state of mourning that, contrary to custom, she never left. She substantially retired from public life, although she continued to perform many of her official duties, such as writing correspondence and conferring with government ministers.

By 1864, Victoria was still in a state of considerable seclusion from the world at Osbourne House, and in desperation her personal secretary, Henry Ponsonby, decided to summon down John Brown, who was a ghillie (outdoor servant) at Balmoral. Victoria and Albert had purchased their Scottish Balmoral in 1848 and had spent numerous happy vacations there before Albert’s death. Albert had liked Brown, and later assigned Brown to attend Victoria, and Ponsonby hoped that Brown would be a reminder of happier days.

Initially Brown’s job was simply to escort Victoria around if she went for a ride outside, but the two of them struck up a rather unlikely friendship. He was devoted to her, a trait that she found extremely appealing, and as servants from the Scottish Highlands were wont to be, he was extremely informal and outspoken with her, another quality she appreciated a good deal. Consequently, she increasingly relied on him, and he rose in importance in her household, being given charge of the queen’s dogs and the organization of her excursions. When she was working, he often stood outside her office and refused to permit anyone in, no matter how high-ranking (including the royal family). The other servants resented his prominence, and Victoria’s children disliked his casual manner and tendency to boss them around, but Victoria refused to hear any criticism of him. He remained her devoted servant and personal friend until his death in 1883.

The film tells essentially this story. In 1864, he’s brought down from Balmoral, with the vague suggestion that the queen barely knew him (in reality, she was already quite fond of him). From the start of his time at Osbourne House, Brown is presented as being stubbornly loyal to the queen, to the point of insisting that he knows what’s best for her, making it clear that he expects her to make use of his services as a ghillie every day.

Due to Brown’s attention, the queen begins to work through her grief. In structuring the story this way, the film relies on the conceit we’ve seen elsewhere that what an unhappy monarch really needs is a common man to treat him or her with bluntness rather than elaborate courtesy. This is a very 20th century notion, and I doubt that it’s really what helped Victoria work through her grief.

In the film, as in reality, there is growing pressure on Victoria to resume her full duties. The film asserts that there was a growing tide of Republicanism that was threatening to abolish the monarchy, and that Benjamin Disraeli (Anthony Sher), one of the leading politicians of the day, finally figures that he needs to persuade Brown to use his influence on Victoria to get her to return to her public appearances. Brown resists this, fearing that it will hurt the queen to be pressured out of her seclusion, but Disraeli finally makes it clear that the abolition of the monarchy is a worse injury than having to do her job, and Brown reluctantly confronts the queen.

The reality, however, is that there was never a real risk of Victoria being removed as queen. Her seclusion did trigger a wave of Republican sentiment, but it was never very large. Rather, the primary complaint was that Victoria and her enormous family were costing the British taxpayer huge sums of money and that the queen was not providing much in return. There was calls in Parliament to reduce the subsidies paid to the royal family. Her second son, Prince Alfred, reached adulthood during her seclusion, and had to be provided a subsidy, which turned into a major political debate tied to the question of whether the queen was going to start making regular public appearances again. It was the threat of a sharp reduction in the royal family’s subsidies that Disraeli was concerned with.

Brown’s Drinking

Brown was a hard-drinking man. Initially, when he was a young ghillie with a lot of physical duties, his drinking does not seem to have adversely affected him, but as he grew older and his duties became more indoors and sedentary, his alcoholism began to catch up with him, to the disgust of the court. Victoria occasionally had to excuse him from attending her at dinners because he was “bashful”, a Victorian euphemism for completely drunk (suddenly I’m picturing Victoria saying “he’s completely shit-faced”), but it was never enough to make her lost confidence in him.

The film is undecided about this detail of his life. He is shown as drinking frequently, and encouraging the queen to have some whiskey as well, but he is usually depicted as being able to perform his duties, albeit hung-over. However in one scene, as the opposition to him at court begins to mount, he is confronted in the stables by two men who beat him and then pour whiskey all over him, creating an impression that he has gotten drunk and then gotten into a brawl. The clear meaning is that someone at the court is trying to ruin Brown. Her children then try to force her to dismiss him, but she refuses.

I haven’t seen any evidence to suggest that this scene is anything other than the film’s invention, designed to put Brown in peril and to allow Victoria a chance to demonstrate her loyalty to him. If the incident has any basis in fact, Brown is likely to have gotten into a brawl all on his own without anyone at court trying to frame him. This seems to be the film’s way of drawing attention away from his alcoholism, by suggesting that he was never actually drunk. Overall, the whole scene feels quite clumsy.

Mr and Mrs Brown

The central question about Brown and Victoria is the exact nature of their relationship. The two of them became extremely close, to the point that many people began wondering just exactly how close they were. His brusque manner of speaking to her (he frequently called her ‘wummun’) and his habit of sleeping in a room next to hers made many members of the court and many politicians uncomfortable. People began to refer to Victoria as “Mrs. Brown,” and her own daughters referred to him as “Mama’s lover”. But in 19th century terminology, ‘ a ‘lover’ could refer to a man who was courting a woman romantically, and was not explicitly a reference to sex. (Try reading a Henry James novel sometime; his male characters are constantly ‘making love’ to women in parlors and on long walks.)

The obvious question, which historians have not been able to definitively answer, is whether Victoria and Brown were, in fact, sexually intimate. No solid evidence exists that they were lovers, but there is a modest amount of circumstantial evidence pointing in that direction. One of Victoria’s chaplains reportedly made a deathbed confession that he had presided over a private marriage ceremony, but this claim comes at four removes from the chaplain in question and so may just be gossip. The respected British historian John Julius Norwich insisted that the equally respected British historian Sir Stephen Runciman had once claimed to have run across a wedding certificate for Victoria and John Brown in the archives of Windsor Castle, but that when he showed it to a member of the royal family, it was burned. Victoria’s son, Edward VII, reportedly paid a staff member at Balmoral for a large number of “very compromising” letters relating to the queen, with the implication being that there was a scandal at Balmoral to be covered up. At least two people have been claimed as children of the couple. When Brown died in 1883, the queen was devastated, describing it as being much like Albert’s death, and she left instructions that when she died, she was to be buried with a lock of Brown’s hair, a ring he had given her, and a photograph of him, as well as two mementos of Albert.

Contrary to current general impressions of her, Victoria was a very sexual woman. She and Albert had nine children, and people joked that impregnating the queen was Albert’s “great industry”. She wrote in her private letters about their “heavenly lovemaking”, and she ordered the installation of door locks on their bedroom doors, lest the children enter at an embarrassing moment. So the notion that a widow in her early 40s with a strong libido might seek sexual solace in the arms of a servant is hardly implausible.

Most startlingly, her personal physician claimed to have accidentally walked in on the two of them when they were flirting. He saw Brown lift up his kilt and said “Oh, I thought it was here?” Victoria responded by lifting up her own skirts and saying “No, it is here.” The gesture of lifting up skirts was an extremely sexually-charged one in the Victorian period (even more so than it is today), and at a minimum the anecdote shows that they comfortable being quite risqué with each other.

The film, however, passes over the question of their romantic involvement almost entirely. It mentions gossip about the two of them, and includes a reading from the humorous magazine Punch of what purports to be a notice of court life describing Mr. John Brown’s daily schedule in Scotland. (“Mr John Brown walked on the Slopes. He subsequently partook of a haggis. In the evening Mr John Brown was pleased to listen to a bag-pipe. Mr John Brown retired early.”) But the closest the film comes to suggesting anything sexual is a scene in which Victoria enjoys a highland dance at Balmoral; as she wheels around with Brown, she gazes at him in a rather suggestive fashion. Brown’s brother later hints that it’s obvious what the queen wants.

The problem here is that in a film about the relationship between Victoria and her servant, the exact nature of the relationship is left unaddressed. The viewer can infer that Victoria’s potentially romantic attraction to him is a way of alleviating her mourning for Albert, but it’s less clear what Brown feels about her. Connolly’s Brown appears to simply be devoted to and protective of Victoria purely because she is his queen, with little exploration of why he feels this way.

Perhaps it’s unfair of me to expect the film to answer a question that historians can’t answer. The relationship puzzled contemporaries and puzzles us still today. But one of the advantages of cinema, a feature I frequently complain about, is its ability to invent things, and this seems like the sort of film where invention is warranted, because by delicately passing over the awkward question of whether Vicky and Johnny were conjugating the verb, the film has produced a narrative about as unsatisfying as the actual known facts.

Want to Know More?

Mrs Brown is available at Amazon.

There isn’t much scholarship on Brown, but if you want to know more try John Brown: Queen Victoria’s Highland Servant. There is, of course, a good deal of scholarship about Victoria. One volume I liked is The Life and Times of Victoria.

John Brown certainly was Victoria’s lover in all but the literal, physical sense. Though she no doubt got a certain thrill out of being waited on by a handsome and very masculine man and occasionally carried in his arms what she wanted more than sex was to be ‘taken care of’. Albert’s death left her feeling very fragile and vulnerable, she wanted to feel protected, cosseted and beloved and Brown gave her that. The Household complained of Brown’s bad manners and presumption and considered Victoria was giving him ideas above his station. They worried about the talk but none of the people in actual close contact with the Queen and Brown believed for a minute there was anything going on there beyond an unwise favoritism.

LikeLike

“Making love” simply meant courting? Well now Henry James novels are far less interesting…. thanks for that. On a serious note, i always thought it was interesting that people have no problem with making historical fiction about other royals (especially female ones—Marie Antoinette’s a favorite) in very unlikely sexual relationships, but Victoria I of England is OFF LIMITS. I’m not saying it’s true, but from Victoria’s diaries, it’s clear that she was a lady who liked to get it in, so as you said, it’s not implausible that she would have formed a sexual relationship with someone else after she got past much of her grief over Albert’s death. And yet, people would rather not think about her as a real person with human needs.

BTW—i’m going to use “conjugating the verb” as a euphemism from now on (and i’m not even a person who uses euphemisms).

LikeLike

Henry James’ characters spend a lot of time ‘ejaculating’ too—at the time it meant to say something strongly and explosively. But it’s really quite an odd feeling reading about characters making love and ejaculating in Victorian parlors.

LikeLike

Personally I think a lover would have been the best possible thing for Victoria. Unfortunately her ethical system wouldn’t allow her one, in the physical sense anyway. IMO Victoria could never have been so open about her relationship with Brown if she’d felt it was in any way guilty or wrong.

LikeLike

You’re right. The question is how far did she go with him? 19th century women were not taught to think about sex, so it’s entirely possible that he might have fingered her or gone down on her without her perceiving that as sex, since there wasn’t a penis involved.

LikeLike

Perfectly true, we have no way of knowing just where Victoria drew the line. All we can know is she felt completely guiltless and saw no need to hide her affection for Brown from anyone. As far as she was concerned it was an innocent relationship. He probably felt the same. His devotion seems to have been quite genuine and mostly, if not entirely disinterested.

LikeLike

What has not been mentioned is that Ponsonby did not take up his position till 1870, 6 years after the action in this film begins

LikeLike