Tags

Barnsdale, Earl of Huntingdon, King John, Medieval England, Medieval Europe, Nottingham, Richard I, Richard the Lion-Hearted, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Robin of Loxley, Sherwood Forest

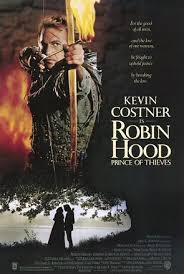

Last year, when I reviewed Disney’s Robin Hood, I avoided discussing the question of whether Robin Hood was a historical figure. I figure it’s time that I tackle another Robin Hood movie, so I chose the infamous Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991, dir. Kevin Reynolds). And I suppose the place to start is with the whole question of the character’s historicity.

Cool! So Is Robin Hood a Real Historical Figure?

No.

Umm…Ok…Could You Go into a Little More Detail?

How do you go into more detail about someone that didn’t exist? By definition, there’s no detail to go into.

Well, Unless You Find More Details to Go Into, This Will Be a Pretty Short Post

That’s a fair point.

The Robin Hood story as we think of it today is set in the early 1190s, when King Richard I, popularly called ‘the Lionhearted’, returned home to his domains after an unexpectedly long absence. Richard had departed on crusade in 1190. Things had gone poorly; the crusade failed in its primary objective of retaking Jerusalem, Richard had been shipwrecked in Dalmatia on his way home, and he had been taken prisoner in the Holy Roman Empire for several years. In his absence, his younger brother and presumed heir John had caused trouble for Richard’s English administration by allying himself with King Philip II of France, Richard’s rival. Richard finally put an end to the political struggles when he returned home in 1194, after being ransomed. So the story as we tell it is set in the period from 1191 to 1194. Most modern versions of the story end with Richard’s return helping to save the day, so we have a fairly clear pair of bookends to Robin Hood’s supposed career.

But the earliest known reference to stories about the outlaw bandit Robin Hood dates from around 1377, when Sloth, a character in Piers Plowman says that he knows the “rimes of Robyn Hood”, meaning that he knows stories or poems about this character. Sloth doesn’t bother explaining who Robin Hood is, which suggests that his audience has at least some idea who the character is because he is mentioned in popular stories. The earliest surviving story about Robin Hood, the poem Robin Hood and the Monk, dates from around 1450. So clearly stories about this outlaw circulated for at least a generation or two before 1377, and then got written down in the mid-15th century. But there’s absolutely no evidence that stories had been circulating for nearly 200 years, as they would have had to been doing in order for Robin to have been active during King Richard’s reign.

The surviving 15th century poems, of which there are about a half-dozen, give us our earliest look at how medieval English audiences pictured Robin Hood, and he is a drastically different character than the modern cinematic figure, so different as to be almost unrecognizable except that several of the names are the same. The stories mention Robin Hood, Little John, and Will Scarlett (or Scarlock), along with Guy of Gisbourne and a sheriff who in one poem is the sheriff of Nottingham. There is also a character, Much the Miller’s Son, who has largely vanished from the cinematic Merry Men. But there is no King Richard or Prince John, only a passing mention of King Edward; nor is there any mention of Maid Marion or Friar Tuck.

Robin and his men are not based around Sherwood Forest, but further north, in Barnsdale in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Robin Hood and his allies use bows and swords, but never quarterstaves. They rob from the rich, but do not give to the poor; in fact, Robin at one point tries to rob an innocent potter and gets beaten up by the man. And there is no mention of taxes, bad government, or oppressive officials; the closest they get to that is poaching the king’s deer and dealing with a greedy abbot. Robin and Little John and Will Scarlett are outlaw bandits, clever enough to trick people, but not defenders of the weak. Robin Hood is devoted to the Virgin Mary, like a lot of figures in later medieval literature. There are a few details that he was murdered by his kinswoman, the prioress of Kirklees Priory, but the story of him marking the place to bury him with an arrow is a later detail not found in the medieval material.

The reference to King Edward situates the stories during the reign of Edward I, II or III, who reigned all in a row from 1272 to 1377. That doesn’t prove the stories originate during that period, but it does demonstrate that the stories were seen to belong to the recent rather than the distant past. There’s just no basis for connecting Robin Hood to the reign of Richard I or John.

So what we have here are vague, generic stories about bandits who bear little resemblance to the modern characters, doing their deeds about 200 years too late for the modern stories. So Robin Hood isn’t a real person; he’s a character out of late medieval folk lore.

The modern statue of Robin Hood outside of Nottingham Castle

Ok, But That Doesn’t Mean There Wasn’t a Bandit Named Robin Hood

You’re going to make me do this the hard way, aren’t you? It’s not enough to show that someone named Robin or Robert (since Robin is a diminutive of Robert) Hood actually existed. Robert/Robin was a fairly common name in the 13th and 14th century, and ‘Hood’ refers to someone who made or wore hoods, a pretty wide category, given that the hood was a common item of male apparel in this period. In order to say that Robin Hood was a real person, we would at a minimum need to be able to demonstrate that someone with that name had been an outlaw or bandit, and ideally that he had done things suggestive of the literary character.

Think of it this way. In the 27th century, people are going to be wondering if Batman was a real historical person. It won’t be enough to find evidence that somebody named Bruce Wayne existed. It won’t be enough to find evidence that a real Bruce Wayne was a millionaire. They’ll have to find evidence that a guy named Bruce Wayne was a millionaire who fought crime as a costumed vigilante.

19th and 20th century historians dug through records of the period looking for guys with similar-sounding names. And inevitably they found a couple of candidates. There’s a Robyn Hood who served as a royal porter in 1324, but about the only thing we know about him is that Edward II gave him a payment because the man could no longer work. Right about the same time, there’s a Robert Hood of Wakefield, near Barnsdale in Yorkshire. In the mid-19th century, an amateur historian, Joseph Hunter, published a book arguing that these two men were the same person, that he had gotten involved in Thomas of Lancaster’s rebellion in 1322, that the king had outlawed him and then later pardoned him. But that’s nothing more than wild speculation without any actual evidence to support it, and it’s most likely that these two men were different people, neither of them being a criminal. Robyn Hood can be shown to have been in the king’s service for some time, meaning that he can’t really have been outlawed in 1322.

There’s an early 14th century court case involve a Yorkshire man named Robert Hood who injured another man with an arrow. But he wasn’t outlawed for it. So he’s unlikely to be our guy.

Another interesting detail is that ‘Robynhod’ was a surname in Sussex, on the southeast coast of England. The earliest known example of this is a Gilbert Robynhod, who turns up in a tax record in 1296. And the name periodically crops up over the 14th century in that county and in nearby London. But none of these men or women were criminals, and they’re a long way from Yorkshire. (Just because ‘Batman’ happens to be an actual surname doesn’t serve as proof that Batman the superhero is real.) Are you starting to notice that ‘Robin Hood’ and its variant isn’t really a very uncommon name?

The closest match to the known facts comes in 1226, when court record from Yorkshire reports on the moveable goods of a fugitive named Robert Hod. The next year, the man is referred to as ‘Hobbehod’ (‘Hobbe’ being another variant of Robert). He was a tenant of the archbishop of York who had fled his holding because of an unspecified debt. That’s all that’s known about this man. But he’s a very weak candidate for Robin Hood, because he’s not a criminal, merely someone who fled a debt and apparently had his property confiscated. Although this man was based in the right general area, and the archbishop did hold lands not very far from Barnsdale, there’s nothing else to connect him to the stories that emerged probably a century later. One would think that if this man had been an impressive enough criminal that poems were still being recited about him 150 years later that he would have left more of a record in the sources of his time.

But Robin was the Earl of Huntingdon, Wasn’t He?

Let’s not get silly now. Nobles turned bandit outlaws? Does that even seem plausible?

The stuff about the earldom of Huntingdon was made up by a 17th century author, Martin Parker, whose gimmick for his Robin Hood poem was that he was going to tell the real story about Robin Hood (you know, the way that modern movies keep claiming they’re going to tell the real story about King Arthur or whomever). Parker claimed that Robin died in 1198 and is mentioned on a tombstone.

The basic problem with this claim is that the earldom of Huntingdon was a noble title that the kings of England sometimes granted to the kings of Scotland. In 1165, when William the Lion became king of Scotland, he passed the earldom to his younger brother David, who held it for the rest of his life, even after he became king of Scotland; David died in 1219. So there’s no opportunity for Robin Hood to have been earl of Huntingdon in 1198. As a historian, Parker wasn’t very concerned about facts.

Ok, Well, Everyone Knows that Robin Hood was Actually Robin of Loxley

Everyone knows that because it was made up by Roger Dodsworth in 1620, a little after Parker made up his story, and another local author claimed in 1637 to have identified Robin’s birth place in Loxley. Dodsworth didn’t bother offering any evidence for his claim. He also claimed that it was Little John who was the earl of Huntingdon, so his historical reliability wasn’t any better than Parker’s. Loxley is a real place in the West Riding of Yorkshire, but there’s no evidence that anyone in the Middle Ages associated it with Robin Hood. There may well have been a ‘Robert Hood of Loxley’ at some point, but that’s just a coincidence of names.

But What about the Evidence for His Burial?

Wow, you’re really grasping at straws, aren’t you? In the late 18th century, a professor of Greek at Cambridge, Thomas Gale, claimed he had found an old epitaph for Robin Hood. The epitaph tells us that Robert earl of Huntingdon was a great archer that people called Robin Hood, that he was an outlaw with his men, and that he died on 24th of December 1247. But the epitaph is written in fake Middle English and so is therefore almost certainly a forgery, probably by Gale. Another problem with the epitaph is that in 1237, Earl John of Huntingdon died, leaving his estates to his four daughters. King Henry III bought the estates and the title that went with them and never granted the title out again. So there was no earldom of Huntingdon in the 1240s.

Yes, there is a supposed tomb of Robin Hood near Kirklees. But an examination of the site with Ground-Penetrating Radar found no evidence of either a body or any ground disturbance associated with burials. And the tomb site is too far away from Kirklees priory to fit with the story of the bow and arrow anyway. And besides, it’s a FAKE. It was erected in 1850 by George Armytage, who owned the land at the time. Armytage used Gale’s supposed epitaph to make his fake monument look more real. 19th century landowners were given to putting up fake ruins and monuments because they thought it would look cool.

The Kirklees ‘tomb’

Back in 2003, an amateur enthusiast conducted some rather imprecise “tests” with a bow and arrow and claimed to have pinpointed the location of Robin Hood’s grave at Kirklees within five meters. He found evidence that a body may have been dug up there in the 18th century, but this proves nothing except that using a bow and arrow to try and locate historical graves is a silly thing to do.

Darn!

Yeah, sorry to bum you out. But when you start digging into the poems, it quickly becomes clear that they’re fiction. The Geste of Robyn Hode (“the deeds of Robin Hood”) is the most substantial of the poems. Robin won’t eat a meal until he has an unexpected guest, who turns up in the form of a desperately poor knight. The knight tells Robin that he had to borrow £400, a truly enormous sum in medieval terms, from the Abbot of St. Mary’s Abbey in York, to bail out his son, who is a criminal. The knight is worrying how he will repay it, but Robin just happens to have £400 laying around, meaning as a bandit, he’s pretty damn wealthy. So he loans it to the knight, who is able to pay off the debt and recover his mortgaged lands. Then Robin has another unexpected dinner guest, a monk of St. Mary’s, who just happens to be carrying £800. The monk lies to Robin, claiming that he barely has any money at all, so Robin takes it all, concluding that the Virgin Mary has sent the money to reward Robin for his generosity. When the knight shows up, having somehow raised another £400 and intending to repay Robin, Robin tells him not to worry and gives him another £400 because he’s just a stand-up guy that way. (This is about as close as the medieval Robin Hood gets to “giving to the poor”, but in this case, he’s giving the money to a knight, who isn’t actually poor by the standards of his day.)

Then Little John sneaks into the service of Sheriff of Nottingham, who is impressed with his archery skills. John persuades the sheriff’s cook to help him steal the sheriff’s treasure, and then lures the sheriff into the forest where he’s taken prisoner and generously allowed to dine off his own stolen plates. When the sheriff gets free, he lures Robin into a trap with an archery contest where the prize is a golden arrow. John is injured and he and Robin wind up taking refuge with the knight they helped earlier in the poem. The sheriff captures the knight, but Robin rescues him. At that point the king (who is not named) and his men ride into the forest disguised as monks, and Robin winds up receiving them at dinner and holding an archery contest in their honor. Eventually the king’s identity is revealed, he pardons Robin and his men because they’re good guys, and he takes them into his service, even going so far as to wear Robin’s green livery. But a year later, Robin gets bored and goes back to being a bandit. The poem ends with a brief story about how his relative, the prioress of Kirklees Abbey, plotted to murder him. She offered to bleed him and just didn’t stop. So the poem ends with a story about how Robin Hood was buried with his bow and a request for a prayer for his soul.

It should be clear from this summary that the poem is a wild fantasy. Robin just happens to have an insanely large sum of money lying around to loan out to the knight, and his generosity is rewarded later on when he recoups twice the sum from the monk, only to give half of it away again. The story relies on comic inversions (the bandit given his captive money, the sheriff dining off his own stolen plates, the bandit hosting the king, the king wearing Robin’s livery instead of the other way around) and the idea that moral decency is rewarded while villainy is punished. The hero is an incorrigible outlaw, and just throws away the king’s pardon because he’s bored. The whole thing reads like a contemporary comic action film, and honestly has a way better plot than Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves does.

Additionally, the historian Maurice Keen, in his Outlaws of Medieval Legend, points out that the Robin Hood poems of the 15th century share many of their motifs with stories of other medieval outlaws. The detail about the monk who is robbed because he won’t tell the truth comes straight out of the story of the 12th century pirate Eustace the Monk. In a different poem, Robin Hood disguises himself as a potter, a retelling of a story variously told about Hereward the Wake, an 11th century rebel; Eustace the Monk; and William Wallace. Keen shows how many elements of the Robin Hood poems are expressions of peasant discontent and in that sense act as a form of social protest. So looking at them for historical facts is probably the wrong approach, sort of like looking at modern action films for historical facts.

So, Basically, What You’re Saying is that Robin Hood is Just the Medieval Version of Batman?

Yeah, pretty much so, except without the plane and the utility belt.

Sort of like this guy

Want to Know More?

The place to start is J.C. Holt’s Robin Hood (Third Edition). It’s a really good exploration of the historical issues with the Robin Hood legend. But if you want to dig a little further, take a look at Maurice Keen’s The Outlaws of Medieval Legend

, which discusses Robin Hood as well as several other real and folkloric outlaws.

One more thing that contributed considerably to the formation of the Robin Hood legend as we know it in the 20th century was Sir Walter Scott’s 1820 novel “Ivanhoe”. The novel included Robin as a supporting character under the name “Locksley”. It was really that novel that placed Robin Hood’s story in the time of King Richard and the crusades. It also established the popular Saxon/Norman rivalry that would become a mainstay of the legend. In fact at the time of it’s release I believe PRINCE OF THIEVES was considered unusual in that it was the rare Robin Hood film to not include that plot element.

LikeLike

Yes, Ivanhoe is definitely important in the evolution of the Robin Hood legend. Scott played a major role in shaping the Medievalism of the 19th century, and we still live in that shadow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One more tidbit for you. David of Scotland, the Earl of Huntingdon did in fact have a son named Robert. Of course he died young so little is known about him in the sources I looked up. However there was a real Robert of Huntingdon, so it’s possible that’s where Martin Parker got the name for his “real identity” of Robin Hood.

The 1980’s BBC series “Robin of Sherwood” capitalized on this and had both Robert and his father David appear in it. It’s also interesting to note that David and his brother William sided with Richard and Elanor of Aquitaine in their 1173-74 rebellion against Henry II.

LikeLike

I’m afraid I’m skeptical of this claim. I can’t find any reference to this son. Robert Oram’s biography doesn’t mention him, nor does Wikipedia or any of the genealogy sites I checked. The Wikipedia page for David’s wife Matilda mentions that the couple had three children who died young: Malcolm, Claricia, and Hodierna, so that page seems to offer an accounting of their offspring. If they did have a son named Robert, he must have died in infancy. But this site: http://fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/SCOTLAND.htm#_Toc389122939

documents their known children and makes no mention of a Robert.

Also, it’s worth pointing out that ‘Robert; was not a named used by the Scottish royal family at this point (although ‘Henry’ wasn’t either and that the name of their only surviving son.)

So my guess is that this Robert is a fictional invention of someone, perhaps “Robin of Sherwood”, who was trying to account for the fact that the earldom of Huntingdon belonged to the Scottish crown in the 1180s and 90s.

LikeLike

That’s funny, the wikipedia page on David I checked does mention a Robert who died young.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David,_Earl_of_Huntingdon

LikeLike

This page here also mentions a son named Robert who died young.

http://fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/SCOTLAND.htm

LikeLike

Ah. We’re looking at two different Davids, David I of Scotland and his grandson, David of Huntingdon. My bad.

LikeLike

No problem. By the way did you see the other Robin Hood movie from 1991 that starred Patrick Bergin and Uma Thurman?

LikeLike

No. It didn’t get cinematic release here in the US, so it’s never been high in my radar.

LikeLike

Yeah here in the US it ended up appearing on Fox TV even though it was made to be a cinema release. Rumor has it it was forced out of cinemas by PRINCE OF THIEVES. It’s pretty much a retread of the classic Errol Flynn film, just done in a more gritty fashion. It also keeps the Saxon/Norman rivalry absent from Costner’s film. In an unusual twist the villains are renamed the Baron Daguerre (Sheriff of Nottingham) and Sir Miles Folcanet (Guy of Gisbourne). It’s never been made clear if this was done to distance the movie from PRINCE OF THIEVES or if the filmmakers thought it would be more historically accurate to give their Norman bad guys French names.

In an interesting historical twist Robin is given a supply of long bows to use as a secret weapon against his adversaries. In the film the bows are made by a welsh bowman named Emlyn. This actually sparked a debate amongst some friends over whether or not the long bow was in fact created by the Welsh or not. As well as a debate over when the long bow was first created.

LikeLike

One last comment on the novel “Ivanhoe”. In the afterward to the 2009 graphic novel “Outlaw: The Legend of Robin Hood”, Allen W. Wright, who runs the website http://www.boldoutlaw.com, had this to say:

“In 1819, Robin gained new fame as a supporting character (Locksley) in Sir Walter Scott’s novel “Ivanhoe”, the most popular book of it’s day. And a curious thing happened. Robin borrowed the biography of the lead character Sir Wilfred of Ivanhoe. Sir Wilfred was a knight returned from the Crusades, a Saxon who fought against Norman tyranny, and a hero who rescued his lady love from a castle. The original Robin Hood wasn’t any of those things, but the TV and film Robin is often all of those things.”

LikeLike

Both the Arthurian Romances and the Robin Hood stories, as well as the Lord of the Rings of all things, have links, or at least references, to a particular medieval family, which French academics call the (Breton) Sovereign House.

William the Conqueror was aided by his father’s double-cousin, Eudon Penteur. This assistance led to “Eudon, Lord of Brittany” being added to the Song of Roland (Norman French version).

Eudon sent two sons, Alan Rufus and Brian, with a large number of soldiers who fought at the Battle of Hastings. Wace and one early text of Gaimar praise Alan’s contribution.

Brian led in at least three battles in 1069, including the Battle of the River Taw against two of Harold’s sons and an army they’d raised in Ireland, and the very hard-fought Battle of Stafford against a combined Welsh and English army. He disappeared after this until he signed a charter in Brittany in 1084. It’s often said by historians that he was severely injured in battle.

Eudon went by the title Penteur (Head of the Clan) and his wife was Orguen of Cornouaille. Already you can see an influence on later Arthurian legend.

Alan went on to become the greatest man in England after the King, having defeated numerous rebel barons in both England and France on the king’s behalf. Perhaps his finest hour was the victory in summer 1088 against the majority of Norman magnates led by his arch-rival Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and backed by Normandy and Flanders. When the crowds were baying for the rebels’ blood, William was inclined to hang them all, but Alan interceded to have them pardoned, offering to return the lands he’d seized from them. Odo was exiled for life.

In 1091, Alan was with the King at Dover when the English army sailed for Normandy. It took half the duchy before Duke Robert “Curthose” came to the negotiating table to concede additional territory.

Alan contributed also to the economy, law and political developments in England, but there’s insufficient time to relate all that here and now. At his death, apparently in the London fire of 1093, his epitaph claimed that England was distraught. This may not have been an exaggeration, because Alan had, alone among the great barons, promoted the English (Angles, Danes and Cumbrians) while excluding Normans, even royal sheriffs, from his lands in the North. In 1093-1094, King Harold’s orphaned daughter Gunhild declared her love for Alan to the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Anselm.

The epitaph describes Alan as “Stella ruit … rutilans, secunda a rege”: a star has fallen ruinously … with red-gold radiance, second to the King. I think this refers to not only to Alan’s hair colour but also to Arcturus, protector of the Bears, Ursa Major and Minor, just as Alan was captain of the household knights who guarded William I and II. Moreover, Arcturus is adjacent to Virgo, whereas Alan wore ermine, the symbol of both Brittany and the Virgin Mary, on his surcoat and banner.

In this poem (it’s in Leonine Hexameter) Alan is twice called “flos”, a flower, implying the rose, another of the Virgin’s emblems, as his Breton name is Alan ar-Rouz. The motto of the Dukes of Richmond, a title deriving from Alan’s foundation of Richmond Castle, is “En la rose, je fleurie”: I flourish in the rose.

Other parts of the epitaph refer to Roman, British and even Persian history.

Alan, it was written by a near contemporary, had “no offspring of his body”. This leaves open the possibility that he may have adopted someone. Howbeit, he was succeeded by his brothers Alan Niger (who I think, for genetic reasons, was a half-brother: both Alan’s parents had red or gold hair) and Stephen, in whose time Bretons such as the Bruces and Stewarts migrated to Ayrshire in Scotland.

Stephen’s grandchildren include William de Tancarville, hereditary Chamberlain of Normandy, who trained and knighted Sir William Marshal, and Duke Conan IV of Brittany. Conan’s grandson Arthur I was passed over for King of England on the Marshal’s advice, but when reports got out that John had murdered him, the Angevin empire fell apart.

Another descendant of Stephen’s was Arthur de Richemont whose claim on Richmond was set aside by his step-brother Henry V, leading ultimately to Arthur taking control of the French crown’s finances and military and reforming them along Breton lines, then leading armies to expel the English and, with his nephew Duke Peter, ending the Hundred Years War.

Thomas Malory wrote his Arthurian tale at the end of Arthur de Richemont’s life, when he was Duke Arthur III of Brittany.

The tale of Potter Thompson places Arthur and his Knights under Richmond castle.

Some Robin Hood stories refer to the castle and others to St Mary’s Abbey York, also founded by Alan Rufus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

PS: Conan IV married Margaret of Huntingdon. Their daughter Constance married Geoffrey, son of Henry II. Arthur I was their son.

LikeLike

Sir Walter Scott of course was no Saxon: he was currying favour with the vain Hanovers.

The name of Ivanhoe doesn’t even look very Saxon: it’s more reminiscent of Bretons such as Saint Ivo of Kermartin (patron saint of really clever lawyers who refuse to submit to the dark side, despite attempted bribery and coercion) or Nevenoe, who led the Bretons to victory against Charles the Bald and the Franks in the battle of Ballon in 845.

LikeLike

Pingback: Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves: Cheerfully Disregarding the Past | An Historian Goes to the Movies

Pingback: Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves: Cheerfully Disregarding the Past ... - SecuritySlagsSecuritySlags

Hey Andrew, I don’t see any review of Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood. Are you planning on reviewing it? I was re-watching it today and as much criticism as the film received, I like it very much (Cate Blanchet, Max Von Sidow and Russell Crowe? What’s not to love!) I was particularly interested in the buildings (layout of “Nottingham”, and the French fleet at the end.

LikeLike

I will get to it eventually. Not sure when, unless someone makes a donation and requests it.

LikeLike

I donated, remember 🙂

LikeLike

Oh, yes! My bad–I’m moving my whole apartment and I’m forgetting anything that’s not immediately in front of me. So I will get to that as soon as I can. Right now, I don’t even have Internet

LikeLike

I don’t envy you the moving –exciting but so stressful. Hope all goes well 🙂

LikeLike

We’re 90% moved, but there’s lots of little things that need to happen, like getting internet transferred and cleaning the old apartment.

LikeLike

Pingback: Robin Hood: A Whole Lotta Plot Going On | An Historian Goes to the Movies

As an fellow historian, I applaud your effort to shed light on this subject. However, for a more thorough and scholarly treatment of the Robin Hood legend, I suggest you check out American historian Melvin Kaminsky’s definitive 1975 work, “When Things Were Rotten.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember that show from when I was a kid. Didn’t even make it a season.

LikeLike

Holy Men in Tights, Batman!

LikeLike